The Genius of G.K. Chesterton: How Borges Led Me to “The Blue Cross” (Part 2)

Investigating One of the Genre’s Most Unique Stories

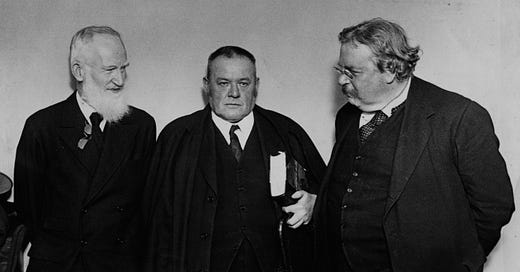

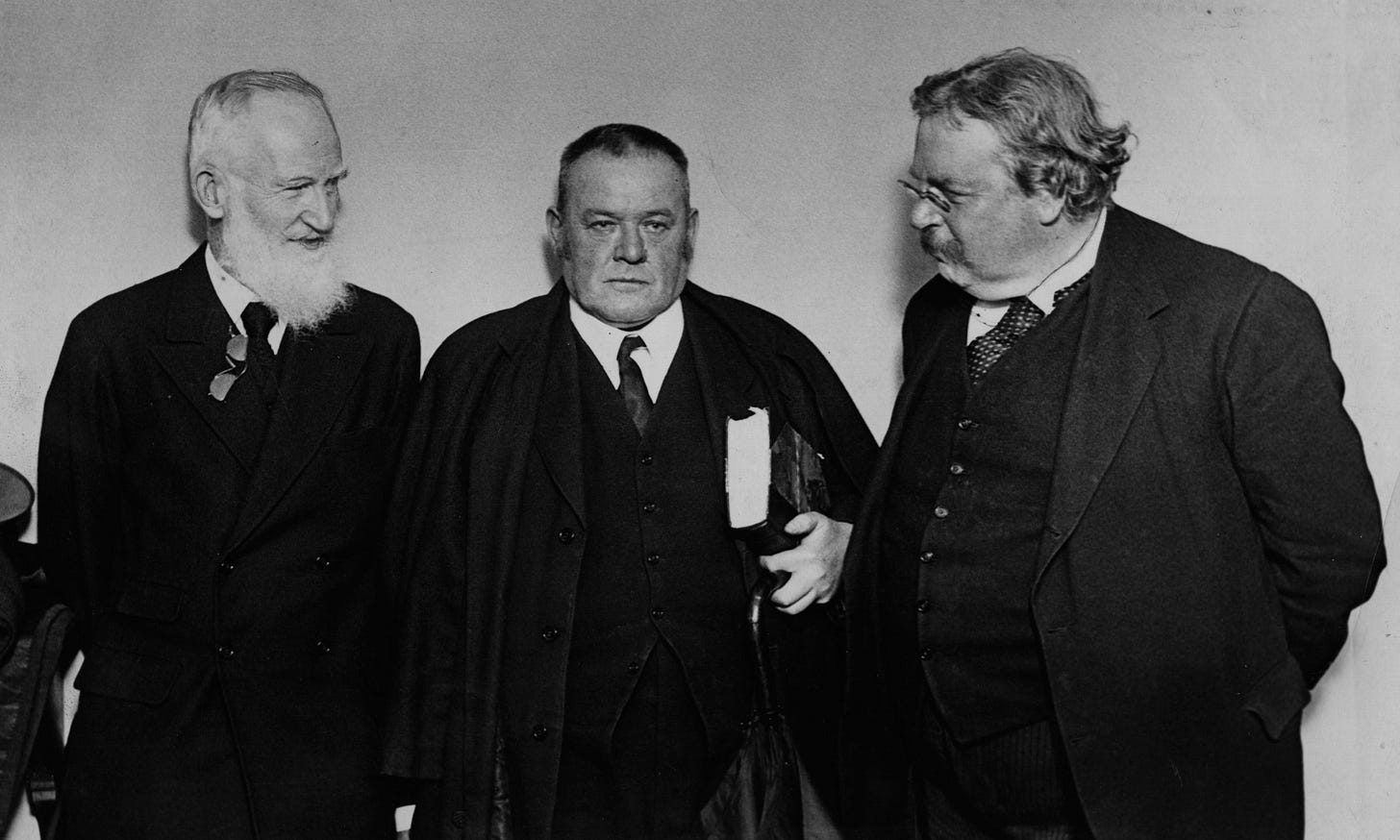

In the first part of this essay I related how an old friend, Borges, led me to the jovial G.K. Chesterton, providing some biographical details about him and others related to his Father Brown character, like the Irish priest on whom it was partly based.

Today’s concluding part is concerned with language, seeking to provide a close analysis of the plot and particularly, Chesterton’s marvelously unique writing in “The Blue Cross” (with some unexpected anecdotes from literary history emerging too).

The essay’s final reward, as promised, is the link to an exemplary audio performance of the story by English voice-actor par extraordinaire Simon Stanhope, owner of the YouTube channel, BiteSized Audio Classics. (If you’re on Bandcamp, visit Simon’s Father Brown album page there for recently re-recorded takes on five other Chesterton classics).

“The Blue Cross” as a Literary Work (Spoiler Alert!)

If before my exegesis you’d like to enjoy the story ‘cold,’ then read it here, or listen to it at the YouTube page at bottom (almost an hour’s listen). Otherwise, let us now begin.

Plot summary: The super-sleuth of the Continent, Parisian police chief Aristide Valentin, travels to England on the trail of Flambeau, suspecting that the cunning international thief will be casing out a clerical conference in London for its valuable ecclesiastical treasures. After crossing the English Channel and getting on the train, Valentin overhears – and reprimands – a simple-minded little priest who has told a woman he’s caring for a valuable silver cross studded with blue jewels…

The priest, of course, is Father Brown, but since this is the first story in the series, his importance is known to neither the (original) reader nor to Valentin- which makes it a unique (i.e., non-repeatable) aspect of the plot and thus unique within the future series. This fact might help explain why this particular Chesterton story so appealed to Borges.

From here, Chesterton begins the major structural innovation of the story: the inversion of events, which in turn opens up philosophical discussions of causality as variously argued.

Whereas typical genre stories feature a detective searching for clues to solve a crime that has already taken place, in this story, the detective is confronted by an illogical series of odd events, clues perhaps, but no crime to be investigated.

At the story’s conclusion, when Flambeau at last is caught out, it becomes clear that Father Brown has surreptitiously orchestrated the set of odd events in order to keep Valentin on the track from an advance distance. It is both an ingenious ruse for an accidental, peripheral assistant-detective, but in other ways a metaphor for the presence of the Divine in human affairs. It is an affirmation of the sort of everyday miracles that Chesterton fully embraced in his theological works.

The extraction of meaning and reassembly of logical order from the apparently disordered series is the triumph of reason. And this is essential, for both the story and again, for Chesterton as a thinker: “you attacked reason,” Father Brown tells Flambeau, when explaining how he knew the disguised thief was not really a priest. “It’s bad theology.”

The Entertainment of Accumulated Clues

The peregrinations of Valentin around London comprise the bulk of the story. This is used by Chesterton for entertaining with examples of causality; Father Brown has a preternatural understanding of Valentin’s singular process of deduction, and so creates a series of apparently meaningless events in the manner that would be of meaning to only this French detective.

Thus, at a restaurant where the sugar and salt containers have been mischievously switched, Valentin is told that the odd stain on the wall was left by two priests. The waiter informs that the shorter one (whose description Valentin matches with that of the priest on the train with the silver cross) had flung his soup at the wall before abruptly leaving.

The trail across London includes similar shenanigans at a greengrocer’s, where Valentin learns the short priest switched signs, and upset an apple cart. The detective enlists two London policemen and continues to another restaurant, disfigured by a star-shaped crack in its window; he learns from the waiter that the short priest had overpaid and when asked what the ‘tip’ was intended for, stated that it was for the window he was about to break, before merrily breaking it and rushing off again with the tall priest.

Then, the proprietress of a sweets shop relates to Valentin that the two priests had been there as well- the shorter one having returned to say he’d forgotten a parcel and asking for her to mail it if found, which she did. Valentin and the policemen finally find the two priests as dark approaches, on Hampstead Heath, and lie in wait while Father Brown engages in a theological discussion, and then tells Flambeau that he has recognized him as a thief. Flambeau believes he has already stolen the parcel from the apparently simple priest, but is wrong, the real cross having already been sent safely by the woman at the sweets shop.

Having executed his duties and accused Flambeau of “bad theology,” Father Brown states that he is aware three policemen are near – for he himself has led them there, with his trail of odd clues – and that there is nowhere to run. Flambeau makes an elegant grand bow to Valentin, ever the sport and the showman, but the Parisian policeman defers the credit, as Father Brown blinks around like a mole, ever modest and inaccessible.

Chesterton’s Vision of a French Detective and Stylistic Innovations

Early on in the story, Chesterton describes Valentin in a unique way that draws on his readings of Voltaire, Poe, Belloc plus other personal and literary experiences. What is interesting is to note, as I mentioned in the first part of this essay, how aspects of his philosophical and non-fiction argumentation converge in his fictional prose, coupled with references to genre developments at the same time Chesterton was trying to break into the business.

As such, he describes Valentin thus:

“Aristide Valentin was unfathomably French; and the French intelligence is intelligence specially and solely. He was not “a thinking machine”; for that is a brainless phrase of modern fatalism and materialism. A machine only is a machine because it cannot think. But he was a thinking man, and a plain man at the same time.”

Here we must note that Chesterton (whose story was appearing in 1910 in the Saturday Evening Post) was taking a shot at an established Post writer of detective stories, American author Jacques Futrelle, whose character Professor Augustus S.F.X. Van Dussen was indeed nicknamed ‘the thinking machine’ for his application of pure logic to solve cases.

This chess-master character first appeared in the 1905 story, “The Problem of Cell 13” (in The Boston American), and was reprinted in a book of detective stories entitled The Thinking Machine in `907.

As always with Chesterton, his criticism was not personal but philosophical, and perhaps he would have not included the Thinking Machine reference had “The Blue Cross” been published two years later than it was.

That is because Futrelle was last seen alive, stoically smoking a cigarette with John Jacob Astor, on board the sinking Titanic, having forced his wife Lily to get into a lifeboat.

As is so often the case when it comes to literature and the people who make it, you could not make this stuff up.

Continuing his description of Valentin, which is designed to carve out a new persona for a detective capable of inhabiting his own thought-world, Chesterton adds:

“All his wonderful successes, that looked like conjuring, had been gained by plodding logic, by clear and commonplace French thought. The French electrify the world not by starting any paradox, they electrify it by carrying out a truism. They carry a truism so far—as in the French Revolution. But exactly because Valentin understood reason, he understood the limits of reason. Only a man who knows nothing of motors talks of motoring without petrol; only a man who knows nothing of reason talks of reasoning without strong, undisputed first principles. Here he had no strong first principles. Flambeau had been missed at Harwich; and if he was in London at all, he might be anything from a tall tramp on Wimbledon Common to a tall toast-master at the Hotel Metropole. In such a naked state of nescience, Valentin had a view and a method of his own.

In such cases he reckoned on the unforeseen. In such cases, when he could not follow the train of the reasonable, he coldly and carefully followed the train of the unreasonable. Instead of going to the right places—banks, police stations, rendezvous—he systematically went to the wrong places; knocked at every empty house, turned down every cul de sac, went up every lane blocked with rubbish, went round every crescent that led him uselessly out of the way. He defended this crazy course quite logically. He said that if one had a clue this was the worst way; but if one had no clue at all it was the best, because there was just the chance that any oddity that caught the eye of the pursuer might be the same that had caught the eye of the pursued.”

These paragraphs alone illustrates what I stated in this essay’s first part: that Chesterton is not a writer of detective literature, he is a writer firstly of literature. All of the features of the logical and poetical argumentation that are found in his other types of writing are combined here, in new ways and toward a new purpose. At the same time, they continue to support his general theological and epistemological position. In Chesterton, we see detective fiction elevated to the position of philosophical literature.

Chesterton’s Contribution to the Genre

And this is very important to note. When approaching what was to him a totally new genre, detective fiction (by 1910, a fairly well-trodden path), he did not need to invent gadgetry or novelty characters- though that was very much what many others in the genre were doing for simply market purposes. Chesterton brought something unique to the genre simply by remaining his own man.

The fact that he has a priest for a peripheral detective is thus actually the least remarkable element here. Rather, the fact that he brings over rhetoric, knowledge and stylistics from completely different genres and somehow makes them work in what had previously been a fairly uniform genre is what makes “The Blue Cross” so special. Had Chesterton never written another detective story, it would still be as valuable as it is to literary history.

Structure and Imagery

Chesterton was a painter and most of his mysteries involve strong visual images that are also symbolic, generally with some philosophic or spiritual dimension to them. And he weaves this into his narrative in ways that have structural sense. For example, the beginning and end of “The Blue Cross” have the same recurring motifs of color into his overarching structure. Take the opening line:

“Between the silver ribbon of morning and the green glittering ribbon of sea, the boat touched Harwich…”

That opening line alludes to the blue cross as a physical object, and starts the description of Valentin’s arrival in morning. Later, near to the final scene on the hill, it has become evening; along with the predictable, daily inversion of time, the color motif is repeated in a new setting, and reflected in metaphysical confirmation informed by reason, as Valentin and his colleagues gather in the dark to overhear a strange theological discussion between the ‘two’ priests:

“They did not find the trail again for an agonising ten minutes, and then it led round the brow of a great dome of hill overlooking an amphitheatre of rich and desolate sunset scenery. Under a tree in this commanding yet neglected spot was an old ramshackle wooden seat. On this seat sat the two priests still in serious speech together. The gorgeous green and gold still clung to the darkening horizon; but the dome above was turning slowly from peacock-green to peacock-blue, and the stars detached themselves more and more like solid jewels.”

Again, this is the sort of ‘real’ writing that fascinated readers like Borges, and which helps draw the story together from a structural perspective. No wonder Borges loved it!

I could go on all day about neat turns of phrases, comic jests, and other ‘Chestertonian’ elements of the story, but I think it’s rather enough. Better to just let you enjoy the story.

So, thanks for reading, and please enjoy “The Blue Cross” as narrated by Simon Stanhope on his BiteSized Audio Classics channel.

I read The Blue Cross some years ago. You brought me back to that experience as I wandered through the story but less prepared than the French detective and thus somewhat lost. It was a pleasurable experience, as is reading your investigation.