The Genius of G.K. Chesterton: How Borges Led Me to “The Blue Cross” (Part 1)

Celebrating the Merry Master of Spiritually-inclined Mystery

Recently, the television offered yet another modern detective series: the BBC’s Father Brown. After watching, I was unsurprised when the Internet confirmed that the 10-year series is only “loosely based” on the original Father Brown mysteries by G.K. Chesterton. The show seemed somehow derivative of Midsomer Murders, but lacking the wry humor of either actor John Nettles in the latter series, or of the humorous writing of Chesterton’s classic stories: in short, an indecisive series marred by anachronisms and the forcible inclusion of modern social issues to a period setting that was not even the original period of the author, as this critical article explains.

Yet production compromises aside, all publicity is good publicity, and if the current BBC effort leads more people to read Chesterton (as the previous ITV 1974 series did, and even Alec Guinness’s first film portrayal of the priestly detective did in 1954), than so much the better.

I’m just a bit cross because G.K. Chesterton and his writings never entered my consciousness until a few years ago, when I started to take a new interest in detective stories- and even then, only accidentally. These wonderfully-written tales were never a part of school curricula, reading lists, nor recommended by anyone. And that is a shame because, while there are many authors of detective literature, most do not qualify firstly as authors of literature.

Chesterton is different. He is what we call a ‘real writer,’ as Jorge Luis Borges might have said.

How Borges Introduced Me to Chesterton

A few years ago, I discovered this Open Culture article, which states that in 1985, “Argentine publisher Hyspamerica asked Borges to create A Personal Library — which involved curating 100 great works of literature and writing introductions for each volume.”

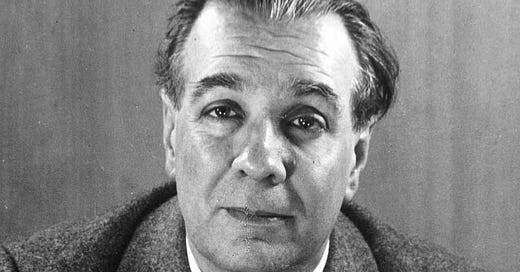

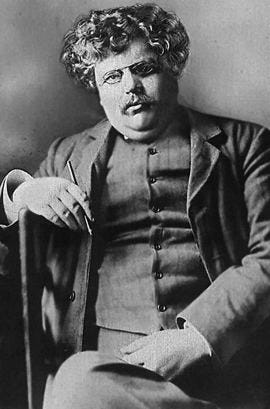

The charming Chesterton

As one of my longtime favorite authors, and one of the most subtle and discerning intellects of the 20th century, Borges and his Personal Library were of course immensely interesting to me. Although he made only 74 selections before his death, Borges did provide a predictably eclectic list of texts ranging from poems and short stories to scientific and sociological works to the Bhagavad Gita, Histories of Herodotus, tales of Edgar Allan Poe, and The Decline and fall of the Roman Empire. Although his entries were ordered numerically, there is no indication that this refers to order of preference.

Despite all the exotic abundance of unknown titles on the list, the one that jumped out at me for some unknown reason was number 5- The Blue Cross: A Father Brown Mystery, by G.K. Chesterton. I had never heard of either the story or the author but felt compelled to learn more. I found the story easily enough; and, even better, an exemplary narration by British voice actor Simon Stanhope, on his YouTube channel BiteSized Audio Classics. (I’ve previously highlighted Simon’s readings in the TLS newsletter, and his rendition of the story will be provided in the second part of this essay for your listening pleasure).

The Borges-Chesterton influence was recorded well before Borges even took on the ‘personal library’ challenge in 1985. He had singled out Father Brown as a source of inspiration in his own works, decades before that. This means that the addition of “The Blue Cross” to the 1980’s list does not represent an inclusion made late in life, but should rather be understood as an enduring favorite which Borges would not fail to commemorate in his final reflections on literature, with that Number 5 listing.

Robert Gillespie’s Contribution to the Case (1974)

Before moving on to Chesterton himself, let me acknowledge some scholarly writing on Borges and Chesterton, as it will demonstrate the long-existing nature of this point of reference.

An article by scholar Robert Gillespie (“Detections: Borges and Father Brown,” in NOVEL: A Forum on Fiction, Vol. 7, No. 3, Duke University Press, Spring 1974) gets to the origins of the influence, and considers it from more points than I can relate briefly. (It is worth reading for anyone with a serious interest in either author). Gillespie cites a book by Borges I have not yet read:

“In Other Inquisitions, 1937-1952, Jorge Luis Borges affectionately mentions G.K. Chesterton’s Father Brown stories and hints that along with Poe’s they are influences on his own stories of mystery, crime and detection.”

A brief bibliographical note.

Other Inquisitions, 1937-1952 was translated into English by Ruth L.C. Simms and published in the University of Texas Press’ Texas Pan-American series in 1964. Borges’ original Spanish version was published in 1952 as Otras inquisiciones (1937-1952) by SUR, and if you read Spanish, it can be found on Amazon here.

Gillespie first proposes that a better understanding of Borges’ stories lies in “looking at Chesterton’s priest, the way both authors experiment with conventions of the mystery genre to examine the supernatural and the nature of evil.” These are all eminently reasonable suggestions and, along with the fascination of both writers with paradoxes, microcosm-macrocosm and the nature of reality, make for good points of investigation.

It may be an accident of history that Chesterton’s detective resembled in some ways the reserved, shy Borges himself. For Gillespie, the ‘unprepossessing’ and ‘dough-faced’ detective of Chesterton’s imagination appealed in his singular plainness to Borges: “the perfect figure for the butt of a joke, Borges sees Father Brown is also the perfect figure for getting in the way and solving metaphysical jokes.”

Another point that would have fascinated Borges, coming from a Catholic country like Argentina and perennially focused on competing explanations of rationality, myth, religion and philosophy, was Chesterton’s authorial choice of a Catholic priest for his protagonist. However, he is no ordinary one. Gillespie has this to say about Father Brown:

“He works by reason and faith, and the two are never at odds owing to a middle sense, intuition, which keeps him from acting mistakenly even if truth is not revealed to his intellect: he has a mystic’s cloud on him when evil is near.”

This subtle integration of faith and reason with an arbitrating ‘middle sense’ of intuition is a fantastic innovation in the history of the genre. It might not be completely unique to Chesterton, as (aside from the plenitude of ‘psychic detectives’ out there), it could be argued that Christian hagiography (both Western but especially Eastern Orthodox) incorporates intuition on the parts of saints or blessed souls to solve otherwise seemingly intractable and baffling mysteries.

Father Brown as a literary character also takes on a sophistication that exceeds that of more famous literary detectives, just owing to his life situation. Gillespie cites this as well. Thus, while being a celibate priest adds to Father Brown’s remoteness from common human experience, Gillespie points out that the character is still “thoroughly a gentleman,” and points out that “the traditionally distinguishing features of the gentleman – power, rationality, and responsibility – mingle in Father Brown with the spy’s invisibility and unreality.”

The last of these, ‘unreality,’ would certainly have captured Borges’ attention, and we will see that all of these character qualities make their appearance in key moments in “The Blue Cross.”

Borges who ranked “The Blue Cross” at no. 5 on his list

Further, Father Brown’s love of “obscure, unique oddities and trinkets make him a perfect Borgesian character,” the scholar notes.

Who Was G.K. Chesterton?

Gilbert Keith Chesterton (29 May 1874 – 14 June 1936) was born in London. His father, Edward, was an estate agent; his mother, Marie Louise (Grosjean) was of Swiss-French ancestry, a factor that certainly played a role in Chesterton’s later affection for French culture which, in combination with his friendships with figures like the Catholic novelist Hilaire Belloc, influenced both the direction of his Christian faith and the esprit of his literary characters. A talented visual artist, Chesterton attended art school but turned to writing instead, working as a London newspaper columnist after the turn of the century. In 1901 too he married Frances Blogg, a devout Christian, who also influenced his Christian beliefs strongly.

Chesterton had started out by working for two London publishers between 1895 and 1902, before quickly becoming prominent for his own columns and books. He had a great wit and sense of humor, and with his tall, bulky and cheerful manner was instantly recognizable. In an extraordinarily diverse career of over 30 years, Chesterton would pen thousands of newspaper articles, several plays, poems, treatises on writers from St. Thomas Aquinas to Charles Dickens, Christian apologetic texts, and novels that imagined a future London (The Napoleon of Notting Hill, 1904) and comic-metaphysical thrillers (The Man Who Was Thursday, 1908). During the last four years of his life, Chesterton was also a popular host on BBC Radio.

However, despite all of his contributions to philosophy, theology, literary criticism, social and political debate and so on, today it is the detective stories of ‘the little Essex priest,’ Father Brown, that have best endured. There are several possible reasons for this – aside from the statement that everyone loves a good detective tale – though I believe there is a certain reason for why Chesterton’s genre fiction resonated so well with readers, many of whom do not share his acquired (1922) Catholicism.

Part of this appeal is perhaps because Chesterton’s unique style is sufficiently idiosyncratic, borrowing from such diverse influences, that it tends towards discursive statements that test the established rules of everything but fiction. While above all, Chesterton is a lover of humanity despite all its fallibility, his merry tendencies to throw together everything – the painter’s visual symbols, the evangelist’s allegories and parables, the logician’s neat traps of contradiction – that he sometimes comes across as baffling. Is he being a philosopher, or just a sophist- or is he just having a laugh at our expense?

An indicative textual example (not from the detective series) refers to one of Chesterton’s famous intellectual friends, of which he had many. A charming and very English characteristic of Chesterton’s was his zeal for debate and the allowance for agreeing to disagree- a rare enough concept today.

Thus, though they often disagreed, Chesterton and George Bernard Shaw were good friends and enjoyed debating. Here is an example of Chesterton’s unique logic, at Bernard Shaw’s expense, taken from his first major Christian apologetic book, Orthodoxy (1908). Chesterton argues:

“The worship of will is the negation of will. To admire mere choice is to refuse to choose. If Mr. Bernard Shaw comes up to me and says, "Will something," that is tantamount to saying, "I do not mind what you will," and that is tantamount to saying, "I have no will in the matter." You cannot admire will in general, because the essence of will is that it is particular.”

Tracing Father Brown: All Roads lead to Tipperary

The very first Father Brown story actually appeared in the US, in The Saturday Evening Post, on 23 July 1910, under the rather too obvious title “Valentin Follows the Curious Trail.” This was reprinted in England as “The Blue Cross” in the September 1910 issue of The Story-Teller. In 1911, it was the lead story in Chesterton’s first full collection of detective stories, The Innocence of Father Brown.

The story introduces not only Father Brown, but also Paris police chief Valentin, a master puzzler of the most difficult cases, and his nemesis, the gentleman-thief Flambeau, a master of disguises who can conceal everything except his great height (like Chesterton himself, Flambeau is six-foot-four).

But what was the inspiration for the character of Father Brown? While commenting on the current BBC series, the Birmingham Post related that Chesterton’s close friend (and one of the key people behind his Catholic conversion), Fr. John O’Connor of Bradford, was the basis for the character. He was a close friend of Chesterton’s from 1904 on. And this native of Clonmel. Co. Tipperary was not shy about the connection, even citing it in his 1937 autobiography, the year after Chesterton’s death.

The article states that “O’Connor is the subject of a biography - titled ‘The Elusive Father Brown: The Life of Monsignor John Joseph O’Connor’ - in which author Julia Smith suggests that his encounters with poverty in Victorian Bradford were an important influence on Chesterton’s Father Brown novels, according to the Bradford Telegraph and Argus.”

The priest was apparently “horrified by the scenes of poverty and vice he encountered in Bradford’s slums. Chesterton, too, was taken aback by his friend’s reports of his experiences and subsequently drew on them for inspiration,” the story relates.

In this concern for social justice and poverty, Fr. O’Connor bore similarities to contemporaneous Irish authors like Pádraic Ó Conaire (covered by the TLS here) and the playwright Sean O’Casey, whose depictions of the paradoxes of war, nationalism and urban poverty characterize his literary vision.

The historical figure of Fr. O’Connor and his post-1904 friendship with Chesterton is also important in another way, as it reveals the author was not simply trying to ‘invent’ a new type of detective at a time when doing so would be entirely expected: in the increasingly competitive and varied Golden Age of the mystery and detective fiction era, new characters and concepts were coming out frequently (as we have already discussed while covering L.T. Meade and her collaborators).

In Chesterton’s case, an unsuspecting author befriended an Irish priest who had both the street knowledge and intellectual acumen to make the whole idea plausible. He had studied at the English Benedictine College at Douai in Flanders, and then did philosophy at the English College in Rome. Said to have had a great intellect, Fr. O’Connor was a good conversationalist who could keep up with Chesterton’s rapid wit and indeed, and spark his imagination.

Aside from the Irish influence on Chesterton’s fictional ‘Essex priest’ this historical anecdote demonstrates how a specific case of an actual clergyman’s pastoral outreach provided harrowing ground-level insight to the sophisticated literary urbanite Chesterton. If not the source of all the author’s actual ‘research,’ Fr. O’Connor might well have been partly responsible for stoking Chesterton’s zeal for analyzing the tragic, the sinful and the simply misfortunate events of human nature from a composite theological and psychological viewpoint.

In the second, concluding part of this essay, we will take a closer look at The Blue Cross, and its unique plot, with a basic focus on highlighting Chesterton’s careful use of language and character construction.

I thoroughly enjoyed this submission as I am a great fan of English detective mysteries including Father Brown. I've read four of the five collections, missing only "The Wisdom of Father Brown." (I'll now look for that too.) Chris is correct that the current TV version is far from the texts. But there is a previous TV version, aired in 1974 starring the late Kenneth More as the Father. It does not strictly follow the books either -- it makes the thief Flambeau into a friend and private eye of the priest. But in its presentation of Father Brown, it is more authentic. [See https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Father_Brown_(1974_TV_series)]

Btw, I am preparing a SubStack of my own on (mostly) English detective books and TV versions.

Even by your high standards, Chris, this is exemplary. It felt like having a glass of wine with a well informed friend . I had no idea of the Borges connection , always minded to seek out Chesterton and now you have convinced me I should.