L.T. Meade: The Great Abandoner of Bandon for Fame Abroad (Part 2)

Part 2 on innovative author L.T. Meade rewards with recitations, style notes and travel tips

Tuesday’s Part 1 of this celebration of Irish Victorian author L.T. Meade discussed her biography, role as an editor and author of stories for girls, and more recent rediscovery by anthologists and scholars of Irish women’s writing.

As it turns out, I have learned a lot since then about this elusive author, thanks to some wonderfully helpful people back in the old country.

Today’s concluding part explores L.T. Meade’s contribution to mystery and ghost stories, written at a crucial point in the development of the detective-story genre in general. These works, very popular in Meade’s own day, were populated by unique and unusual characters, at a time when reader expectations readers demanded that new detectives, villains and plots all have some element of novelty.

The essay also includes some detective work of my own: this week’s research to answer a curious question from the point of view of travel and tourism in an Ireland that is now coming to the end of a very well-planned and long-anticipated ‘Decade of Centenaries.’

That is, despite the efforts by some academics and editors in recent years seeking to re-instate Meade to the canon (something that has started to be done), there is still little trace of the author in the town of Bandon she abandoned for the bright lights of London at the age of twenty-one- or anywhere else in Cork, apparently.

In a country like Ireland that instinctively squeezes every drop of potential tourist revenue from every famous writer with whom it has the remotest of associations, this just seems like a strange and missed opportunity. But, you can judge for yourself at the end.

L.T. Meade: International Woman of Mystery (Somewhat Solved)

One of the most mysterious things about Meade (aside from her own numerous mystery tales) is how relatively little is known of her life or works today. I am sure there are some academics with a very detailed knowledge, but the Internet does not easily give up its treasures on the subject of Meade relative to other Irish writers. This absence is also remarkable, considering just how much she published during and after her lifetime, and how influential she was, that it is not easier to get any sense of the woman herself.

L.T. Meade is like a ghost, haunting the enormous eerie manor that comprises her (un)collected works and (missing?) correspondence.

By revision-time today, I was beginning to lose hope I would get any new leads from such scholars. But my long week on the research trail was finally rewarded, at the last minute.

Acting on a tip from Clodagh Finn (whose 2022 book Through Her Eyes will be covered here later this month), I had reached out to the University of Limerick’s Tara Giddens, an expert on Irish female writers of Meade’s period. Just as I was making this final edit, I heard back from the scholar, who had great news to share. In fact, she had devoted a whole chapter of her PhD to L.T. Meade’s journalism, and her representation of a woman journalist in her novel A Sister of the Red Cross (1902). Finally I had tracked down someone with detailed knowledge of the elusive author.

According to Giddens, this novel “is really interesting as it's a ‘girl's book’ yet deals with some heavy topics like war.”

The scholar further clarified a vague point in Meade’s biography, which in turn confirmed my own semi-educated guess about some of her writing and editing decisions. This is a really interesting point that I had not found anywhere online.

“What's so interesting about Meade is her ability to move with the times,” Tara Giddens continues. “The main breadwinner for her family, Meade had to be very aware of what was popular and publishable, and we see this as she moves away from writing books for girls and begins to write detective stories. Throughout her career, Meade very carefully created a public image of herself as a professional writer whilst still being a maternal figure.”

That is a remarkable statement that in a very few words, informs us considerably of what factors influenced Meade’s writing. We will hear again from the Limerick scholar shortly.

A Quick Note on Style

As a writer, I can say that there’s no way anyone as prolific as Meade was could be so productive without relying on certain formulas, clichés and repeated habits. We all do it, consciously and not. It’s no big deal.

Still, there is something charming about Meade’s now-dated style. It is like the verbal equivalent of an overgrown copse within which a well-appointed period dining table has been set. Meade’s manner of storytelling is, though, remarkably straightforward, even for its era, and compares well with that of other contemporaneous (and more long-winded) authors. One sets in for the trip (a typical mystery story takes about an hour of narration time) and enjoys the journey.

Indeed, we have to give Meade and her collaborators credit for both maintaining plot, pace, and a certain ingenuity of creation in terms of originality of premise and scientific deduction.

Meade’s Place in the Mystery Genre and Legacy in Helping Irish Female Authors

It’s important to remember that Meade was writing during the Industrial Revolution, at a time just after Poe, in his all-too-short life, had blown the doors open to a brand-new genre he had basically created, and shown what might be done with it; but her career was also just before the maturation of the Golden Age of mystery with Agatha Christie in the early 20th century.

Indeed, as Dublin’s Swan River Press reminds concerning Meade as a mystery writer, despite her image as an author for girls, “…in 1898 the Strand Magazine, famous for its fictions of crime, detection, and the uncanny, proclaimed Meade one of its most popular writers for her contributions to its signature fare.”

It is important to remember that when Meade made her savvy move from stories for girls to tales of ghosts and more mundane villains, she had an established network of international contacts in the publishing world, due both to her recent editorship of Atalanta and her active role in the feminist movement. But these activities did not only benefit her own career, and an as-yet-underexplored topic is that of how her publishing stature enabled the work of other female writers at the time. Here too is a point that keeps her linked with her home country, even if it has been forgotten.

Indeed, as the University of Limerick’s Tara Giddens states, “as the editor for Atalanta, Meade actively promoted women's writing (for example, Irish women like Katharine Tynan, Catherine Mary Mac Sorley, and Clotilde Graves) as well as better education and career for women and girls. Additionally, Meade played an active role in women's networks in England, like the Literary Ladies Dinner.”

What L.T. Meade accomplished was to bridge earlier and different genres of fiction with mystery, always with an eye to innovations in the genre’s development by other authors.

She was a contemporary of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle (1859-1930), and like him came up with consistent stories with rational explanations that leave the reader feeling satisfied with the adventure.

Perhaps the only knock on some of her detectives is that they lack the key elements of personality and likeability that later masters. But that is largely because she was writing before the introduction of humor into the genre by (first of all) the French) authors. After all, neither Holmes nor Watson were ever particularly funny either, nor meant to be.

L.T. Meade: Combining Progressive Feminism and Collaboration with Male Authors

Although Meade was a committed feminist, and member of the Pioneer Club, she had nothing against creative collaborations with male authors, as she had built up confidence in her own writing over decades of success. She was also a shrewd business-woman who understood where trends were headed, and where specialized knowledge might benefit her general endeavor. This cooperation led to some of her most famous works.

For example, after a few stories co-authored with ‘Dr. Clifford Halifax’ (more on him later) in 1893, she co-authored The Sorceress of the Strand (a ‘Madame Sara’ story) and The Brotherhood of the Seven Kings with English writer Robert Eustace (the pen name of Eustace Robert Barton, 1854-1943). Both stories featured unusual female villains, including gangland leader ‘Madame Koluchy.’ Meade’s work with Eustace led to further innovations in detective character-creation at a time of maximum competition between authors when the Golden Age was really kicking off; among their most memorable characters is the palm-reading occult detective, Diana Marburg. This palmist was prominently featured in the 1902 story "The Oracle of Maddox Street."

For his part, Eustace (and some believe Meade may have had more two collaborators using this same pen name) enjoyed a long and successful career owing to his scientific background, which was ideal for mysteries and collaborations; indeed, Eustace’s early work with L.T. Meade would lead him later on to get a credit for devising the basic plot for The Documents in the Case (1930) by the very influential and much-loved Dorothy L. Sayers.

Although there are many modern authors influenced by Sayers (and readers of her work), relatively few would be aware of the woman whose co-conspirator, Eustace, had earlier honed his skills with at the turn-of-the-century. As a big fan of history and literary descent, I simply point this out in the hopes that scholars of ‘Sayers studies’ might also become scholars of ‘Meade studies,’ and vice versa.

A Case Study: The Mystery of the Circular Chamber (1897)

I will now demonstrate a magic trick: that is, to perform the lightest touch of literary criticism without giving away any plot spoilers, as this Meade-Eustace work is, after all, a spectral detective story.

The story can be enjoyed at your leisure in the Youtube video below, as perfectly recited by Simon Stanhope of Bitesized Audio Classics.

The Mystery of the Circular Chamber, Stanhope informs us, first appeared in the June 1897 issue of Cassell's Magazine. (It has also been reprinted by Halycon and is available from Amazon here).

By this time in her career, Meade was very well established and also was four years removed from the editorship of the soon-to-be-defunct Atalanta magazine for girls. Having ceased those editorial duties, she had more time to concentrate on developing ingenious mystery plots and this, along with the collaborative ideas of Eustace, a man with a scientific background, made the production of her last two decades distinct.

Anyway, the Circular Chamber is not just any mystery. It appears to be a variation of the locked-room or sealed-room device in mystery, but... It involves a haunted circular chamber at an old English inn, unexplained revolutions, years of vague deaths due to ‘syncopy’ (or, inexplicable fright), the remnants of an old mill, a cantankerous landlord and oddly possessed or possibly epileptic granddaughter. A wonderland of misdiagnoses haunts the environs in which Meade’s characters suspect and fear the worst of one another. And that is not even to mention the main drama of the case.

I also share the Bitesized Audio Classics version as performed by Simon Stanhope, so you can enjoy listening to his masterful reading of the story. (You’ll find plenty of other works by Meade, and a great many other period authors, on his channel, so please do subscribe).

If you recall that I found this channel (and L.T. Meade) during the pandemic, it might amuse you to note that the worse suffering of that summer was having to endure the poor and uninspired narrations found on other audiobook channels out there (I will not mention names). But the experience left me with a newfound appreciation for the art of great performance in narration.

Some Literary Criticism of the Story and Plot Basics

Although the writing style is somewhat perfunctory, and the detective in this case (John Bell, the so-called ‘professional exposer of ghosts’) is rather humorless, the story does move along in its lovely leisurely way. (I suspect that this character’s name could have been a hat-tip to Dr. Joseph Bell, the University of Edinburgh professor who tutored Arthur Conan Doyle, and is widely considered to have been the inspiration for Sherlock Holmes).

John Bell is requested to take a case concerning a young watercolor painter who was found dead at the Castle Inn, after leaving for a countryside commission to do landscape painting.

Bell agrees and (as any clever detective would) calls in at the inn where the dead man had lodged previously, before going to the Castle Inn. This allows an opportunity for the authors to have an outside character voice apprehension of the Castle’s historically haunted nature, and for Bell to scoff it off.

Besides creating a mood of foreboding, this also is important as Bell (under his ‘cover’ as a photographer) is told that he can achieve his ostensible task without even needing to visit the Castle. Of course, he refuses, but it helps lengthen the whole foreshadowing of dread that is meant to be realized at his final destination, while neatly illustrating some of his method.

I will not say much about the characters Bell then meets at the Castle (the landlord, his wife, and their granddaughter), as even the slightest criticism might contribute to spoiling the plot. Just to say that they could have been done somewhat better in different respects.

Finally, the central ingenuity of the mystery – in which Bell must both solve the murder of the young painter, and disprove forever the existence of a ghost at the Castle Inn – is achieved in a robustly scientific way. Again, certain things could have been done better, and in the hands of different authors the whole enterprise might have come off rather differently (I can only imagine Borges’ take), but it all works out in the end.

Bell succeeds in not dying himself (which is always better for the detective!) and a longer, multi-generational mystery is unraveled. The way of final explanation of events contemporaneous with the story’s narrative conclusion resembles some of the narrations in Conan Doyle.

Now That’s What I Call Prolific!

Speaking of the author of Sherlock Holmes, let’s move to a point of comparison.

In her career, L.T. Meade published over 280 books and stories- a staggering achievement by any estimate.

Yet adding to this is the sheer range of tastes and markets to which she was catering; indeed, it is one thing to devote oneself entirely to writing for a certain niche, and quite another to entertain audiences ranging from children to hard-boiled lovers of detective mysteries and ghost stories.

It is indeed a testament to the advanced nature of Meade’s time that publishers would even allow such freedom- today, in the segmentation-obsessed publishing world, it is hard enough to gain a foothold in even one sub-niche of a sub-niche… so much for progress.

In any case, how does L.T. Meade and her almost 300 titles compare to the output of a more famous mystery writer of her time- the equally multi-genre creator of Sherlock Holmes?

Arthur Conan Doyle launched the career of Holmes with A Study in Scarlet (1887). In total, he published four novels and 56 stories featuring the iconic, pipe-smoking detective. Conan Doyle also wrote in genres such as fantasy, comic historical fiction, historical novels, science fiction, poetry, plays and various non-fiction. Altogether, these amounted to roughly 120 non-Holmes stories, and almost 20 novels not involving the famous character.

Now, how do these totals compare with those of the transplanted Irishwoman in London?

Between 1872 and her death in 1914, L.T. Meade published 149 books for ‘young readers’ (the last seven of which were published between 1915 and 1919). Anyone who has ever tried to write a book for children – and, a popular and successful one – knows that this is the toughest audience of all. This achievement in itself would be unsurpassed. But of course, there’s much more.

In the mystery genre, Meade published some 66 stories and books, which appeared between 1893 and the years soon after her death (though one story, The Detections of Miss Florence Cusack, did appear in 1998).

Meade wrote these mystery tales firstly with the aforementioned ‘Dr. Clifford Halifax’ (the pen name for English doctor and writer Edgar Beaumont). Their collaboration began with The Troublesome World in 1893- the first of their six collaborations through 1901. Although information on Halifax/Beaumont is scant, it appears he only used this particular pen name in works written jointly with Meade.

I conclude that, as a savvy writer, editor and observer of literary trends, L.T. Meade began these collaborations as a means of increasing her own knowledge in specialist areas then becoming popularized in fiction (such as medical and forensic input in detective stories).

L.T. Meade wrote many other mysteries on her own, and several additionally with other male collaborators, the best known of which is the aforementioned Robert Eustace. Their first work was 1894’s The Arrest of Captain Vandaleur: How Miss Cusack Discovered His Trick. The partnership continued in eight mysteries through 1903’s The Face in the Dark and the aforementioned “The Oracle of Maddox Street” in 1902.

However, after that, Meade’s final 32 detective stories appear to be attributed to her alone, which indicates that once she had taken whatever input her male colleagues could offer, she set off on her own, ever confident in her own abilities.

L.T. Meade has a further 101 titles in the infamous ‘Other’ category, the publications dates for some of which remain in question. This category starts with A Knight of Today (1877); the partially-posthumous list runs right up to 2010 and Old Rail Fence Corners. Other unique titles from this category that might shed some light on Meade’s views of her home country include The O'Donnells of Inchfawn (1887).

Between 1894 and 1911, Meade also wrote some 11 collections of short stories, further adding to her phenomenal productivity.

It should be said, though, that some Internet references tend to duplicate individual stories that may have appeared in larger collected works; nevertheless, whatever the real total of L.T. Meade’s word-count turns out to have been, it definitely rivaled that of her contemporaries. She had an apparently tireless and ever-creative nature and ability to draw on sundry sources of inspiration. Hers is a life abut which we would like to know more.

“Unfortunately, she still often remains a hidden figure in Irish literature despite her prolific career,” attests Tara Giddens. “However, scholars are actively tracing her career and networks, both in England and Ireland, and it's an exciting time as we continue to learn more about L. T. Meade.”

L.T. Meade’s Legacy Today: Detective Work on the Irish Travel & Heritage Front

From everything I have discovered and discussed in this two-part essay, it seemed plausible that Ireland – and particularly, Meade’s home county of Cork and hometown of Bandon – would have some sort of memorials, if not a whole museum – at least a statue – of this local legend who rivaled in literary output what the town’s 19th-century Allman Distillery gushed out in spirits (600,000 gallons of whiskey a year).

However, an Internet search on Monday revealed nothing, and two phone calls the following day similarly did not resolve the mystery… by Thursday, even the expert scholar from Limerick, and the author Clodagh Finn, had not heard of any Meade-memorials in Ireland.

Considering that Meade was a writer, I had assumed that phoning up the Bandon Library would be the most logical way to start. However, while the librarian was unfailingly polite, she confessed to not being a local and to have not heard of Meade before. My request was sent, I was told, to an expert….

By Wednesday (after Part 1 of this essay had already appeared), I had received more information from the Bandon librarian, regarding the ‘Meade case.’ She revealed that “unfortunately to the best of our information there isn’t any monument to her.”

On Thursday, as I was just wrapping up my edits, I heard from the Local Studies expert who the Bandon Library had forwarded my initial query on to, Louise Mackey of Co. Cork Library. She forwarded on a very helpful 2014 essay on Meade n the Bandon Historical Journal, by Veronica Buckley.

As for the case of the missing Meade memorabilia, Mackey said: “I checked to see if there was any memorial or monument to Meade in Bandon or Cork County and couldn’t find any information on one. It seems that her achievements continue to be overlooked.”

It appears, therefore, that the great abandoner of Bandon has in turn been abandoned by Bandon. But it was not always that way, as further information from the unfailingly helpful Bandon Library librarian, Tina, proved.

Among some recent (and historical) Irish media articles on L.T. Meade that she attached on Wednesday, I was struck by one front-page story from a 4 July 1907 issue of the Cork Weekly Examiner, which I reproduce below. (I hope the picture is big enough to read). This article announces serialization of “The Secret Terror,” by “Mrs. L.T. Meade.” This alone indicates that Meade was actively read (and, very likely, cooperated with editors) in her home county, even long after she left for London.

When in Bandon…

And now for some tourism tips, as that is after all part of the TLS mission.

If there is really no memorial to Meade in Bandon or Cork, it would be quite surprising, especially given the entrepreneurial Irish endearment for naming anything inanimate after local personages or events of interest.

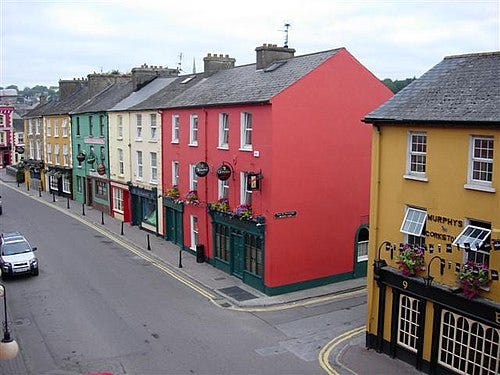

For example, while the ExploreWestCork website lists over 20 historic walks and hikes, none of them are associated with Meade, even in name. The town, located 20 miles west of Cork city on the Bandon River, has grown in recent years, though retaining its neat rural charm…

I propose that at least one haunted, foggy wooded path be re-appropriated and renamed for Meade, as it would be the sort of setting that leaps out of some of her literary settings.

Established in 1588 by Queen Elizabeth 1 as a fort town for the first English plantations, Bandon is now sometimes called the gateway to West Cork. If traveling in the Cork region, visit Bandon for its popular Music Festival (the first weekend of June). August sees both the Bandon Summer Festival and the Bandon Walled Town Festival, which are more family-friendly events.

Even if there aren’t (yet) memorials to Bandon’s most successful literary daughter, it’s still a wonderful and historic place to visit for travelers any time of year, but especially in summer, when it is enlivened by these various festivals.

When in town, also visit the West Cork Heritage Centre, which is housed in the former Christchurch (1610) on North Main Street. (The Heritage Centre is currently taking donations here for refurbishments that will help restore this historic building and make it more functional as a community space).

Further afield, visit lovely Skibbereen, about seven miles from the sea on the River Ilen, its name deriving from the river-boats of yesteryear. It was a place affected by the Great Famine, and the Skibbereen Heritage Centre contains an exhibit on that historical period, as well as many other topics of local interest.

In this town with a name that seems to leap out of a story, I decided to continue the story of my search for more information in L.T. Meade. Thus I contacted the editors of The Southern Star, a local newspaper, to see if they were aware of any local Meade memorials.

Editor Siobhán Cronin recalled having commissioned an article on L.T. Meade in 2014 by UK-based author Robert Hume (which was also forwarded to me by the Bandon Library). This was a good sign that Meade’s local memory has not been forgotten. But Editor Cronin also could not recall any Meade monuments in the county.

She did add, however, that “as our paper is over 130 years old now, you may find something in our archives which can be searched for free here” The term ‘here’ referred to the Irish News Archive website, which is indeed a good resource for future researchers on L.T. Meade (and many other writers and other historical figures and events.

Festivals Investigated- More Literary Travel

I began the week with another question: does Bandon have a literature festival?

Along the Internet roadways, I noted a relic of one apparently former festival: Engage Bandon (apparently held last in 2016). So the answer seems to be not exactly. However, my further detective work bore some fruit.

According to the West Cork Music website, for literature, you’ll need to travel an hour or so west of Bandon, to the lovely coastal town of Bantry for some annual literature celebrations.

Since the Music Festival runs the Literature Festival, I decided to ring them up on Monday and see whether L.T. Meade had ever been mentioned in the festival, or whether there was any local remembrance of her, according to what they might know.

Also very polite and helpful, the Music Festival representative stated that L.T. though Meade was an unknown commodity to him, possibly earlier iterations of the festival (which began in the 1990s) could have mentioned her.

However, a follow-up e-mail from the Festival director, Eimear O’Herlihy, indicates that at least during her time at the event (since 2015), L.T. Meade has not been encountered haunting the Festival.

Bonus Coverage: How to Stay Informed of the West Cork Music and Literature Festival (for 2023 and Beyond)

I imagine, however, that given the new interest from the Irish media, anthologists, academics and prestigious private publishers like Swan River Press, it should not be much longer before a Meade ‘re-haunting’ of her ancestral lands occurs, in the literary sense or even wrought-iron form. I stick with my suggestion for a haunted trail in her honor, at least.

The one bit of literary-traveler news I can reward you with for now is this: subscribe to the festival’s free newsletter here and be informed of the upcoming 2023 line-up within the next couple of months. The list also provides current news on concerts being held right now in the local area.

In 2022, the West Cork Literature Festival line-up included Zadie Smith, Colm Tóibín, Áine Ní Ghlinn, Rodaan Al Galidi, Suad Aldarra, Rachel Andrews, Aisling Arundel, Alex Barclay, Sara Baume, Mark Beatty, Lynn Buckle and Gonchigkhand Byambaa.

Included in this literature fest, usually held after the Chamber Music Festival, are the ‘Masters of Tradition’ workshops. They even take requests. Speakers in these 2022 sessions included Jane Casey (on crime wiring) and Paul Muldoon on poetry.

So, this wraps up for now my celebration of the lost legend of L.T. Meade, an author who – as I wrote in the beginning of Part 1 – came to me only by accident, because of the pandemic in 2021, and via the wonderful narration of Simon Stanhope on the Bitesized Audio Classics channel.

I am glad that, in continuing this literary adventure, the story has also expanded and introduced me to several new people and places in Ireland, including a great music and literature festival. I am incredibly grateful to all of these Irish people for their patient and kind assistance on short notice- a wonderful research experience and I wish them all the best of luck.

Should anyone inform me of Meade-related memorabilia lying about the shop, or any apparitions encountered, I will be sure to let you all know.

I finally got a chance to listen to The Mystery of the Circular Chamber. A very nice read and well voiced. Thanks for the tip.

What a pleasant trip through distant Irish byways. And, no, Holmes & Watson were hardly ever funny.