Dear readers,

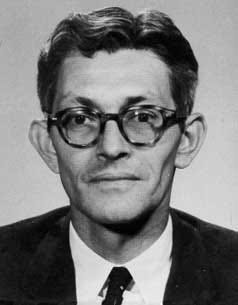

today’s story, in six short parts, is fictional—and not based on the exploits of legendary CIA officer James Jesus Angleton (Dec. 9, 1917-May 11, 1987). That he died 37 years ago today is probably also a coincidence.

The following is something of a ‘period piece’ story, with hints of a murder-mystery, and a slow-burn espionage caper all in one. So pour yourself your favorite beverage, and enjoy the tale. ‘The Mexico Job’ was written about 2013, and is published today for the first time.

-The Mexico Job-

By Christopher Deliso

1: A FINAL MISSION

Of course Bill was told immediately. Some details were still murky, but he knew enough to avoid the funeral. Larry would have saluted him for that. Never no sentimentality with him.

Well, would have been nice to see that old bastard one last time, Bill mused. But in the end it was neither a bad result nor a worse result; just some housekeeping, another inevitability needing resolution.

Taking his black briefcase, and an old plaid coat he might not need, Bill left his home in Alexandria and drove to Dulles International, for the evening plane to Mexico City. Paid it himself, and a commercial flight too; Larry would have liked that, too.

On the plane, Bill lit a cigarette and gazed out the rounded window, watching the rain-soaked pavement twinkling, ghost-like through his own gaunt reflection. Workers in caution jackets on the tarmac were executing final checks. Routine work. Bill was used to routine work; he admired this as a concept, in the way he had admired Larry as a person. Both men were good soldiers, and they had always stuck to the miission: through bad weather, good weather, and those long intervals when there was nothing to do but wait. Sort of like fishing, in that way, he thought. Funny old job…

As the plane wheeled down the runway, Bill was amused; after all these years he still feared flying. Avoided it whenever possible, though you could not always avoid the things you distrusted. Nor the people.

Relax, people had always admonished him, air travel’s much safer than going by car. Well, JFK would have certainly agreed, he thought, and cackled so hard that the flight attendant turned and looked at him oddly. She was handing out peanuts. He took a packet.

It was almost midnight when they landed. Bill was among the first off. Very few knew about this particular job; he had vetoed any idea of sending a car, not to mention a clean grab from the aircraft. Heck, it would be nice for a change, filing through immigration with the regular folks, waiting for a taxi cab like them, and just going on his own. Anyway, he was retired, and even if just for good-housekeeping, this trip would almost certainly be his last. He’d already suffered the obligatory retirement cake, but he was tired now, too.

Suddenly, Bill was struck by an almost forgotten youthful feeling, the one from the early days of the job; that feeling of exhilaration, of danger, of venturing into the great and perhaps hostile unknown of arriving at a foreign city at night. And this rush provided temporary cover for his inner exhaustion and old age. He felt it when he scanned the airport’s police and its crowds, when he memorized the earring design of the bored woman inspecting his Virginia driver’s license, when he navigated the unreadable gauntlet at Arrivals, where stoic greeters held signs requesting various names that were not his own.

Outside, in the temperate dark, Bill recalled images from similar nights, ones that bookended his adult life: the frigid silence of Moscow, the Gulf’s saline oil reek, the torrential rainscape of Hanoi, and Tokyo’s neon omniscience.

It had always struck Bill as ludicrous, the way presidents and senators and diplomats went about their business, what with the rolling victory salutes, the flapping little flags, the phalanxes of bodyguards, flashbulbs and fashionable speeches recited from lofty podiums. And none of it mattered, not in the end, not even in the moment. And yet for all their trappings, none of them had any real power. Their lack in this respect satisfied Bill something terrible, he thought.

Because the end always came, sometimes more efficiently, sometimes less so, but people like that were not the ones who controlled it. People like him were the ones who controlled executable outcomes, and to a large extent that involved being invisible. If the last ten years had confirmed anything he already had learned from the previous twenty-three, it was that in this business you could not expect anything to be done by that class of folk. You do it yourself, you do it quietly, and you definitely do not ask anyone for favors or for permission. Because favors is what gets you killed, and permission is what gets you fired. So many people had forgotten these rules. They were always the ones that got themselves exposed.

2: TO THE VILLA

Bill saw a green Beetle on the curb and waved at the cabbie standing there. He got in and wedged his briefcase between his feet, and folded his coat across his lap. When asked for a destination, Bill paused- not because of the language, but because his memory was slower now. Then he remembered the restaurant on the boulevard below Larry’s villa, and put a name to the street; the cabbie nodded and set off.

Larry had been among the longest-serving station chiefs in any single location. Bill had gravely warned him a few months before that according to his sources, the Mexicans were planning to erect a statue of him. He laughed out loud. Well, Larry certainly had been a fixture. A regular piece of the furniture down here. And he had always been accommodating. But behind his amiable Louisiana drawl was a mind as cunning and as cold as that of the most successful politician or killer. The two men saw eye to eye on most matters, though they did sometimes argue over the executable details.

Bill and Larry had done some very good work in the villa’s secure basement. They could talk and plan in peace there, shoot pool and drink bourbon too. The bourbon was brought down by Larry’s wife- more sullenly or less, depending which wife it was at the time.

The latest one, the Mexican girl, was the nicest, but she had also been the most exasperating, for Bill anyway. She was the daughter of a Mexican general and so it had taken months to get her approved—despite Larry having already been retired by then. Larry, who hated waiting for anything, naturally took it out on Bill, who himself was kept in the dark, as a part of routine business.

At Larry’s exasperated and impatient complaints, Bill had joked that had he been as rigorous in vetting the first three wives, perhaps he could have saved Larry a lot of grief, and money. Larry had bristled like an old boar, stubborn and stuck in the tangled thicket that is human relationships. But he was cordial again after Bill had cleared the bramble. And Bill had come for Larry’s final wedding, too. Pity, he thought, that after all that trouble the old drunk had died just at the necessary time.

3: ASSESSING A DEATH

The cab stopped at the boulevard, by the small shops bef a restaurant that Bill noted was still open. He paid the fare and went out into the Mexican night. He turned upwards along the side-street and, after ten minutes of walking along a grassy, wooded hill, finally reached the villa. Puffing hard from the exertion, Bill took the tiny key from his pocket and opened the gate. He could hear the fountain, gurgling from the expansive lawn. That was where Larry had presided so splendidly over so many routine garden parties. All of it for the greater good, Bill chuckled.

He walked up the flat stone path to the main door and knocked. After a minute there was Octavia, the Mexican girl, thirty-four and vivacious and not looking terribly bereaved. She was a slim, dark-eyed beauty and she smiled widely from beyond the threshold, the backing pale light painting her almost angelic. With a theatrical sweep of the wrist, she welcomed Bill by name.

“Jack!” she beamed. “You made it safe! Please, come in.”

Bill smiled and went in. He thought about apologizing for her loss but it seemed like too much of a good thing; he had already expressed his condolences over the phone that afternoon. Anyway the young-enough widow appeared reconciled to her inheritance.

“Not to impose. Just need to see about some things”-

“Jack, you know you are welcome. Anything you need,” said Octavia. “You were so kind to me and my dear Larry. I am happy to help. But you must be hungry? Please, sit down.”

Bill protested that he had already eaten, but she was adamant. As they entered the dining room, he scanned every detail, seeking out anything presenting a possible contradiction or future threat to the Agency.

“Well,” he remarked, gazing across the room. “This household is positively sparkling. Reckon you have some fine maids.”

“Maids?” Octavia retorted. “I do everything here! Well, not this week. So busy with the funeral. I am sorry. Larry would never even let me dust his bookshelf! Can you imagine, Jack?”

“No, no I can’t,” Bill said, and coughed. He had to think quickly.

“I’m being most sincere. A lovely, well-kept home,” Bill said. “Tell you what—why not tomorrow morning, you dust that bookshelf nicely, as a sort of tribute to old Larry? We both know he was such an avid reader. Just… keep it to yourself. Let’s say, a private tribute.”

“Alright, Jack. I will dust it tomorrow,” the widow replied.

Bill adjusted his thick black spectacles as he observed her discreetly.

“Tell me, Octavia, have any of… our people stopped in since… well, eh, you know?”

Octavia paused in mid-step. She had put on an apron, and was carrying a pot.

“No, and I don’t understand why!” she lamented. “I could not imagine it. I was downtown that day, and when I came back I found my Larry, covered with blood, dead! It was horrible! I called for an ambulance, and they took him, but too late. Of course I called the American Embassy, but no one has come! I was very afraid someone might… you know… suspect that I was somehow”—

“Oh no, don’t worry,” soothed Bill. “Not a chance of that. Everyone knows you had nothing to do with this terrible tragedy.”

The old man shook his head, pretending to sympathize. Of course no one had come; Bill had personally ordered the ambassador that no one was permitted to enter that villa until further notice. Or harass the poor widow. Routine business, he had explained.

“And as you said to the Embassy people, there was only the one broken window? And nothing was touched or stolen? Is that what the police saw?”

“Yes, yes. I had it fixed. I have so many questions, but the police have not told me anything! Nothing from your people, either!”

Well that’s just not right,” Bill said, shaking his head in feigned paternal sympathy. “I will tell them. Any help you may need”—

“Oh thank you, Jack,” the widow said, relieved. “I have so much to do! All of those papers, and his things. Maybe his children in America will want”—

“Don’t worry,” interjected the old man, with a magnanimous smile. “The Embassy will provide full assistance, and if there’s anything else you may need, or a question they can’t answer, please telephone me directly.”

“Oh, Jack, thank you so much,” Octavia said, with a slight bow as she set out his food. “Now, please, enjoy- I made some rice and beans, I am sorry it is nothing special, but I didn’t know you are coming until the evening. But, tomorrow for the breakfast you”—

“I’m so sorry, ma’am, but unfortunately I’ll have to miss your breakfast, though I know from past experience it would be very fine,” said Bill. “My flight home leaves in a few hours.”

“Oh! What a shame!”

4: CONDOLENSCES AND COLLECTIONS

“Yes, it is a shane, Octavia, I do apologize. Don’t worry about old Jack. Just get your rest. I am sorry to have kept you up this late,” Bill continued. “Tell me, would you know where Larry’s paperwork might be located?”

“Yes,” the Mexican woman replied. “My husband always kept everything in the safe. But I don’t know how to open it.”

“That’s just fine,” Bill said, trying not to frown and examining her closely. This was the sort of detail that spouses were not supposed to know; the villa had been modified in a certain way for a reason…

“You’re sure that whoever committed this despicable murder of your husband, did not also open, or try to open, the safe, yes?”

“Of course not,” Octavia replied vigorously. “It’s impossible to see it on the wall, and I saw it had not been disturbed, after.”

Bill examined her quickly and was satisfied that she was not lying.

“For your own safety, should anyone ask you about a safe—you’ll tell them you had no idea of one even existing, and that your husband stored his things in the desk’s drawers in his study, alright?”

“Yes, of course, if you say so, Jack.”

“I will take out everything from the safe and put it in the desk drawers, so that the proper authorities can see for themselves, and give it all to you,” said Bill with a flourish of magnanimity. “And please—no one from either the Mexican or American side should know that I was here tonight. This is all for your safety. I am trying to do you a favor. Okay?”

“Okay, okay, I never saw any safe, and I never saw you tonight!” Octavia laughed, her face betraying intimations of fear as she untied the apron from her waist and put it away.

“I’m most obliged,” Bill said. “Last thing—could you kindly find a little bourbon for me before you go”—

“Of course,” Octavia said. She turned and peered, like a diligent pharmacist, into the liquor cabinet. A splendid little housewife, Bill thought to himself. Took him four tries, but good old Larry almost had it all in the end—a damn foolish thing, how he messed it up. But routine work was something else, and it did not tolerate mistakes, even in retirement.

Octavia poured a large bourbon for her guest, and a small one for herself. Then she unexpectedly and sharply saluted her guest, voicing an old joke used by Bill and her late husband.

“Viva la revolución,” the widow said brightly.

“Viva la revolución,” Bill intoned solemnly, raising his glass.

Octavia drank quickly and nodded. “You’ll take a taxi back to the airport?”

“Yes. Don’t worry about me. And thank you, ma’am, you have been the perfect hostess,” Bill said. “I will ensure everything’s arranged. Our people will take real good care of you.”

The widow smiled, more sadly now. “Really, you are too kind, Jack. I am just sorry we don’t have my dear Larry here with us. We all had such good times together!”

“Yes, we did indeed. I’m sorry about that too.”

“Safe travels, Jack,” she said, and disappeared down the hall into the darkness.

Bill waved and turned to the rice and beans. He finished quickly and washed the plate and silverware. Then, taking the bourbon in his right hand, and the briefcase in his left, he headed into the study.

The hallway was dark but he knew the location of every light—after all, he had personally overseen the team that wired it up, all those years ago. He turned right and bumped the light switch on with his shoulder. The grandly-outfitted study, where good-old Larry had worked, came to life.

Bill set his glass on the mahogany desk, and sank into the leather chair behind it. He waited, sipping his bourbon, listening for the intimate sounds the villa made: the hum of the light, the water, running through the pipes along the wall, the floorboards shifting under her feet in the other room, and then the sound of a blanket being shaken… When he was sure the widow was asleep, Bill pulled out soft gloves from his back pocket and began routine work.

First he checked the desk drawers, which would be, he hoped, of interest to no one. Stacked papers, envelopes half-torn or sealed, a utility bill, and a charitable solicitation letter. So far so good, Bill thought, and then encountered a card reading happy birthday, Larry; it lay prone and unresponsive, like a bad joke lingering on, in the stale aftersmell of the dead cigarette butts crushed down in the gray pouch ashtray that sat on the desktop.

There were pictures, too. A large framed one displayed cheery young people; Bill recalled them as Larry’s children and grandchildren, probably by the first wife. He left everything as it was for the Embassy to deal with.

Then Bill noticed another, older photo, exposed to the touch. Bill chuckled when he recognized himself. It was the two of them, on one of their fishing trips. Why, that must be the Russian River up in California, he mused. Probably, twenty years ago, the Steelhead run. Well before the big mess started. Larry had caught a nice big trout that day, Bill recalled and chuckled. The photo was yellowing and dulled on the edges. He put it in his briefcase out of respect.

5: SAFE-CRACKING AND BOOK-SHELVING

Satisfied with the desk, Bill rose to the safe. It had been built, practically invisibly, into the wall and adjoined the imposing bookshelf, and was further concealed by a triumphal portrait of James K. Polk, conqueror of Texas. Well that was Larry’s contribution, chuckled Bill. A wicked sense of humor, he had.

Removing the portrait, Bill easily opened the safe. The legal documents were indeed untouched. Octavia had been straight with him; at least there was that. Bill put the documents on the desk, leaving the pistol in the back of the safe, wrapped in its old cloth. He separated the minutiae from the important things that she would actually need: the insurance information, the villa deed, the boat registrations, the Florida house deed, and the letter from the New Orleans lawyer who could provide counsel regarding the last will and testament of one James Lawrence Ransom Lattimore IV.

Bill separated the necessary things from those that were not, as Larry would have done, had he not been so careless. But he had, and now it was on Bill to make everything appear, or disappear, as it should.

He scattered the minutiae in the desk drawers amongst the bulk of envelopes, and put the important documents in the bottom drawer, as he had promised Octavia he would.

Then, from his briefcase Bill removed two long manila envelopes, gripping them delicately, as if they were sluice boxes and he was panning out gold from the river bed. Inside these envelopes was money, plenty of it, and various grainy photographs, of different people, or several people, and all of them would be understood as problematic for someone’s interest somewhere. Other photos revealed obscure machinery, and even perhaps a Soviet warplane at rest. Some of the pictures had rougher edges than others. Some were stained, and some just looked old. But they did all look authentic.

The manila envelopes also contained letters, some handwritten, others typed on thin paper bearing various official seals, some in Spanish, some in Russian, some in English. Bill placed all of this curious materiel carefully inside the safe and locked it, hanging President Polk back up in his protective position before it on the wall.

It then struck Bill as somewhat perverse, that one’s own life insurance could best be kept in the locked hold of some dead man’s ship. But it was a funny job. And it would work, when someone not-yet-retired came to take the bait. All you had to do was wait, because fishermen would come. There was no surer thing in the world.

But the one thing Bill hadn’t expected, and for which he felt immeasurably grateful, was Octavia’s off-handed comment about the undusted bookshelf, and his quick reply that she should indeed dust it the next day. He relished how problems sorted themselves out in this mysterious job, if you had patience and luck.

The old man gazed at the bookshelf. It was immobile, but not immense. The books on its thick and ornately-carved shelves were archaic and by subject diverse. Illuminating them with his pocket flashlight, Bill was relieved to see that Octavia had indeed been straight with him: everywhere there was dust; and it had to be a year or more thick, from left to right and bottom to top. At that moment, the dust was the only thing in the world absolutely incapable of lying to him.

In the upper right-hand corner of the uppermost bookshelf, Bill spied his target; Izaak Walton’s The Compleat Angler. He did not know which had been more difficult: for the Office of Technical Services a decade before, to have constructed this case and its false cavity, relying on just a photo; or for Bill himself, just that week, to have acquired the damn three-centuries-old, three-volume first-edition of the classic British angler’s companion. Bill laughed out loud. Sometimes the lengths they took seemed ridiculous, even to him. Funny old job.

With one gloved hand, Bill strained to pull down the upper edges of the book. He slowly angled the top down, until the anticipated deception clarified itself. In the emptiness where a real book should have been, he aimed the flashlight he held in his other hand, training it on the almost invisible hole where the skeleton key would fit. He then unlocked the pane in the back wall, and gazed into the hidden compartment.

There was no way of knowing if the rumor he’d heard was true, and whether Larry had mentioned the false book to that pesky journalist back in Washington. No one had reported anything yet, but there was no point in taking chances.

With his flashlight, Bill illuminated the narrow recess. Thankfully, it seemed unvisited and untouched, for almost ten years now. He saw the soft black satchel and pulled it out. He relocked the pane, covering the key-hole with the bit of wall that slid over it. Then, with a screwdriver, Bill very carefully removed the screws, and the false cover of The Compleat Angler, and put it all in his briefcase. He then filled the wall’s screw-holes with a tiny amount of clay from a small tube in his briefcase; the clay was identical in color to the bookshelf, rendering the sccrew-holes invisible.

In the newly-freed space on the bookshelf’s upper corner, the retired man placed the actual three volumes of The Compleat Angler, published in London in 1676; it had been almost impossible to find on such short notice, had not been cheap, and had barely fit in his briefcase. But of course it fit its appointed spot on the Mexico City villa’s bookshelf perfectly, as designed a decade before.

Bill next turned to the recovered satchel—little more than a jewelry-bag, it would seem to the casual observer. He carefully inspected the documents and photos held in the little bag, transferring them to his briefcase too. Everything that someone would need to disturb the dead—as well as some of the living—was there. Good old Larry. Damned if he didn’t keep his end of the bargain.

Bill reflected, but not too hard, that perhaps Larry hadn’t had to die after all. Probably, the rumors about gossip amd the journalist were false. But why take chances, when the world was such a dangerous place already? Bill paused to admire Larry’s discretion, which had preserved the right guys and been a constant, quiet threat to the wrong guys, the ones who could not be trusted. They would never know, and neither would the American people, of Larry’s final sacrifice. But everyone should be grateful to him for his vigilance, Bill chuckled, statue or no statue.

6: EXITING DOWNSTREAM

Unceremoniously, without nostalgia, the retired man drained his glass and surveyed the room again. Satisfied, he took the briefcase and glass back to the kitchen, nudging the light switch off as he went. He washed the glass, avoiding any fingerprints. Donning his coat, he quietly slipped out of the house.

He was breathing more easily now because the Mexico job was done and because the road back was downhill. For the first time, he felt sadness that old Larry was gone. One more good man down… Too bad he had to go like that, though. Heck, now that I’m out of commission too, I’ll have to go fishing by myself.

Bill emerged from the darkness onto the boulevard, and found a sad-lit small restaurant, somehow still open, despite the late hour. Inside, a black-and-white television was broadcasting loudly a reprisal of that afternoon’s Mexican league soccer match, and the waiters were still watching it even after Bill entered. There were no customers. He ordered beer and paid directly, and asked that they phone him a cab, in excellent Spanish. When it came, the waiter graciously bowed when Bill left the change untouched on the table, not even noticing that the strange late-night customer had taken the beer bottle with him, and neglected the glass provided.

In the cab Bill set his briefcase between his feet, and folded his jacket across his lap as he sipped the beer. When the cab pulled into Departures the old man paid the fare, and tossed the empty bottle into a trash can. He walked back into the terminal just as he had emerged from it four hours earlier, anonymous and alone.

He had a smoke in the dingy, deserted lounge, the routine intermittent announcements providing some companionship. Bill was tired now; indeed, he was almost asleep by the time they called the flight.

The flight was not full. Nevertheless, the old man wedged his briefcase and its secrets tight under his elbow as he slept against the window, with the panel closed tight to block out any sunrise. Bill woke as they landed. The line was short at immigration. He could have skipped the process, but he thought it good practice for a retiree and ordinary citizen.

The old man was waved ahead by a policeman at the booth. He was a thickly-built man of about thirty-five, with a broad honest face that looked to Bill Italian-American. Bill was not wrong.

“Hey, how ya doin’, sir?” said the officer. “Came in on the Mexico City flight?”

“Yep.”

“I just need to see your license,” said the jovial officer. “So what kinda work you do?”

“Work?” Bill cracked. “You flatter me, officer. I’m retired. It’s a full-time job, but someone’s gotta do it.”

“Hey, that don’t sound so bad,” replied the officer, handing back the Virginia driver’s license. “You enjoyin’ it?”

“Could be worse,” deadpanned Bill. “Imagine I’ll spend the weekend fishing again.”

“Hey, you do that, buddy,” said the officer, nodding his broad, honest face. “You do that.”