(Absence of) Vision and the Insights of Two Great Irish Playwrights: J.M. Synge and Samuel Beckett

Or, how an Early Modern Philosophical debate links two literary giants

I admit it- I never knew much about the theatre. I attribute my ignorance of this art form to a childhood (and childish) disdain for acting, and all the silly costumes and stage-pieces that accompanied it.

As a writer, I still cannot imagine the kind of confident a playwright must have, to write down words so magnificent that real live humans would spend weeks of their lives memorizing and then uttering said words aloud before an audience, all sweaty under the inevitable bright lights of a stage set. And then to watch these suffering souls! The whole thing felt like cruel and unusual punishment.

Yet, as they say, the show must go on. So as we reach the mid-way point of February’s special TLS coverage of Irish writing, I’m devoting today’s articles to two of the giants of Irish theatre: two very different playwrights from different eras, yet who in their own very unique and different voices carry on a tradition.

And, as I learned while researching this, it’s not a tradition that might at first appear in your mind’s eye.

Playwright the First: John Millington Synge

John Millington Synge (1871-1909) was a contemporary and collaborator of W.B. Yeats, whose poetry we discussed in the previous article. J.M. Synge was born into a wealthy, bi-national family, but his father died of smallpox, and he himself suffered from ill health; he was thus home-schooled.

Nevertheless, he managed to recover enough to gain a scholarship to Trinity College, Dublin, where he obtained a BA after studying Irish and Hebrew, while also participating in orchestra as a talented multi-instrumentalist. Subsequently, Synge tried to study music in Germany in 1893, before resolving to become a poet in Paris the next year. Like other Irish Literary Revival luminaries, Synge sought to go ‘to the source’ of Irish history and culture, and thus found much inspiration in the wind-blown wilds of the Aran Islands off the west coast, where he gathered anecdotes and stories from the locals and wrote in a small paradise on the sea.

Although he died at only age 37, Synge achieved great success and attention in his own lifetime as a pioneer of Irish plays at the Abbey Theatre in Dublin, an institution which Synge had co-founded with Yeats and Lady Gregory (1852-1932).

His most famous play, The Playboy of the Western World (1907), now considered a classic, was, er, poorly received. At its 26 January premier, a “mob of howling devils,” nationalists protesting its alleged affront to public morals and inappropriate portrayal of the peasantry, ran amuck- the famous ‘Abbey Theatre riots.’

Villanova University’s Falvey Library exhibits an interesting collection of documents related to the Abbey riots.

Synge penned several other notable plays, only one of which concerns our focus today. These include In the Shadow of the Glen (1903), Riders to the Sea (1904), The Well of the Saints (1905) and The Tinker's Wedding (1909).

Vision-Restored and Lost as Concept in The Well of the Saints (1905)

Synge’s lifelong physical suffering and awareness of the suffering of others found artistic expression in myriad ways. Like Yeats, his great contemporary in poetry, he was never content to make simplistic statements. And so is the case with the 1905 play, The Well of the Saints, a sort of parable, yet one with considerable depth, ambiguity and a multiplicity of meanings for the viewer to decide.

According to the Abbey Theatre’s website, the play debuted on 4 February 1905 (that is, 123 years ago this month). I imagine we can expect a reprise in 2025, if not sooner. Given today’s trends in technology, health care and religion, I can already anticipate some of the reviews that will be written by others then.

Set in a mountainous enclave in the east of Ireland, at a time ‘one or more centuries’ before the author’s era, this three-act play concerns an elderly blind beggar couple, Martin and Mary Doul. Through their blighted but happy enough existence, they have been fooled by the townsfolk into thinking that they are both beautiful. However, when a wandering saint cures their blindness with water from a holy well, they are disgusted with each other, seeing themselves at last for what they are.

Undeterred, they seek to take part in village life. Old Martin gains employ with the local blacksmith, Timmy, but is rebuked when trying to seduce his beautiful fiancée, Molly Byrne. The old man is sent away, and both he and his wife again go blind. When the wandering saint returns to perform the young couple’s wedding, Martin refuses his offer to restore their sight, mocking the saint and saying that life without vision is better. The saint is offended, and the locals drive away the bitter old couple. They head south, in search of new neighbors, while the saint marries the young couple.

The play can be enjoyed in an adapted form in this 1975 televised version.

I do not personally know a Synge expert. But in his paper, “The Dramatic Structure of The Well of the Saints,” scholar Nicholas Green does make this interesting historical connection about Synge:

“…Where other plays were based on anecdotes or tales which he had heard, the plot of The Well of the Saints was invented, though the idea may have been suggested by the fifteenth-century Moralité de L’Aveugle et du Boiteux of Andrieu de la Vigne.”

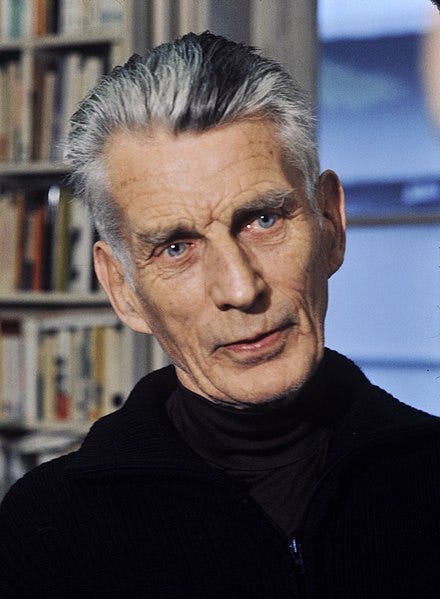

Playwright the Second: Samuel Beckett

While I do not know a Synge expert, I come at this author somewhat better prepared, as here I can count on the expertise of a noted Beckett expert, Dr. Einat Adar of the University of South Bohemia in České Budějovice. In fact, she has written specifically on the issue of vision and blindness as concepts in the Early Modern Irish philosophical tradition, and in terms of its specific application to the works of both Synge and the philosophically-minded later Irish playwright (more from Dr. Adar below).

Today, Beckett’s most famous work is of course, Waiting for Godot, first performed on 5 January 1953, at the Theatre Babylone in Paris.

It was probably the reputation of the play as being one in which ‘nothing happened’ (as well, remember, as my general aversion to theatre) that prevented me from ever seeing this fabled work. I readily admit that Beckett remains one of the most famous Irish authors about whom I know the least. And that is why there is always more learning to be done- something that is an essential part of life, and indeed of this little newsletter. I am so grateful for every little bit that I can continue to learn, and take great satisfaction from attributing it to those who share their knowledge with me for the good of everyone.

Samuel Beckett (1906-1989) was in many ways, a polar opposite of Synge. First of all, he had a long life (missing the year 1990 by just 10 days!) And, while Synge had made travels to the Continent, Beckett actually lived most of his adult life in France, being a member of the French resistance during WWII. He was also firstly a devotee of James Joyce, who would have great influence on his early career especially.

Beckett is considered by some as the ‘last’ Modernist, but also as a key figure bridging Modernism and Post-Modernism, his work (which also included stories, poems and novels) becoming increasingly minimalistic, self-referential and involved with meaning over time.

Born in Dublin, he studied French, Italian and English at Trinity College, from 1923-27. After briefly teaching in Belfast, he became an English teacher at the École Normale Supérieure in Paris from 1927-30. He then returned to teach in Ireland, but gave it up after a couple of years, to his parents’ consternation. Several personal tragedies occurred in the next few years; particularly the death of Beckett’s father of a heart attack in 1933 contributed to his gloom.

His first novel, the autobiographical and darkly humorous Murphy, appeared in 1938, depicting the author’s wanderings in London and conveying his depression and self-doubt at the time. After a strange participation as witness in an Irish censorship trial (not even involving his own work), Beckett became infuriated with Ireland and set off again for France. When war broke out, he joined the resistance and, while he always discounted his heroics, was after the war honored by Charles De Gaulle for his efforts.

In 1945, while back in Dublin to visit his mother, who was suffering from Parkinson’s, Beckett had a revelation about his entire future course. He changed his focus from English to French, and published a story the following year in Sartre’s journal in Paris. He embarked on a furious period of writing and started to become famous. He had expressed a realization that there was no longer anywhere to go down the road Joyce had paved. Beckett’s own vision was completely different: bleak, austere, and minimalist.

He began with a trilogy published by Jérôme Lindon’s Les Éditions de Minuite, Molloy (1951), Malone meurt (1951) and L'innommable (1953). Beckett himself had been too nervous to approach the publisher with the work, so his partner, Suzanne Déchevaux-Dumesnil, who he would later marry in a secret wedding.

Nevertheless, it was the decision to go into theatre and the instant global success of Waiting for Godot in 1953 that would establish Beckett’s status and preserve his finances.

In general, his biography is so extensive and well-documented that it is not for me to write it further here. The Internet is full of great documentaries on his life, such as this one (almost two hours in length), which includes interviews with some of his friends and family members.

Early Modern Irish Philosophy of Vision and Epistemology- Yes, It Is a Thing

And, now at last, we can return to the insights of Dr. Einat Adar. This whole unplanned research adventure ended up as it did solely because of her communications with me 11 days ago. These are the sorts of coincidences that make doing this newsletter so fun and rewarding for me.

Asked for her own commentary for my future piece on Beckett, Dr. Adar gave some advice, and referred me to her most popular work, which she described as a “short exploration of blindness in Irish theatre.”

The article in question, “From Irish Philosophy to Irish Theatre: The Blind (Wo)Man Made to See,” first published in March 2017, examines “the construction of blindness that ‘comes to us’ from Irish philosophy and the ways in which it is worked and reworked in Irish theatre.”

In Dr. Adar’s view, the literary construction of the ‘blind man made to see’ is paradigmatic, in its implications of absence (of the visual sense) and restoration (to a state of normality). However, while conventional wisdom would have it that cured blindness results in a successful normalization of the individual in society, Dr. Adar notes that in Irish theatre, the experience of those so ‘cured’ is rarely so happy. “This skepticism about the ability of the blind to enter directly into the sighted world can be traced back to the writings of Irish philosophers, especially William Molyneux and George Berkley.”

Huh? Yes, that’s pretty much what I said, hearing that. But she actually makes quite a point. After a careful read, I understood why her article is so popular.

In her paper, Dr. Adar explores this concept in regards to four 20th century plays: W.B. Yeats’ The Cat and the Moon (1917), J. M. Synge’s The Well of the Saints (1904), Samuel Beckett’s Rough for Theatre I (1976) and Brian Friel’s Molly Sweeney (1994).

Because of today’s focus, I will only consider the comments on the Synge and Beckett plays; the reader can read the entire linked paper above for Dr. Adar’s exploration of the other two works.

Dr. Adar notes an ‘Irish School’ of philosophers in the broader European Early Modern philosophical period, between 1690 and 1750. On the issue of blindness, she specifies Molyneux and Berkeley.

The context she provides is the apparent recent re-interest in the centrality of vision in Enlightenment philosophy, from Descartes on, as being the prime medium for accessing knowledge and understanding the world. This view, she shows, has been critiqued in modern times by French post-structuralists, as with “…Michel Foucault’s observation in The Birth of the Clinic, that there were ‘two great mythical experiences on which the philosophy of the eighteenth century had wished to base its beginning: the foreign spectator in an unknown country, and the man born blind restored to light.”

Molyneux, whose wife was blind, wrote an important treatise on blindness and in 1688 sent it to John Locke, stipulating the ‘Jocose Problem.’ Known ever since as the ‘Molyneux Problem,’ it asks whether a hypothetical man born blind, who has learned to distinguish by touch a sphere and a cube, would be able to recognize them correctly if he could somehow see.

Berkeley’s response to this problem in 1709; he “contended that the blind man will not even understand the question,” Dr. Adar recounts. “In his first major work, A New Theory of Vision, he argues that knowledge of distance and form is not achieved through direct perception, but derives from a combination of visual cues and corresponding tactile sensations – an ability that must be acquired by experience.”

This interpretation has epistemological implications. “When Berkeley answers the Molyneux problem in the negative, he reinforces its sceptic attitudes towards the possibility of “pure” knowledge that is untainted by prejudice or experience,” the scholar continues.

How does this all apply to modern Irish plays? Let us now consider the two cases.

Philosophy of Vision in Synge

These Irish philosophers share, with playwrights Yeats and Synge, Dr. Adar notes, an interest in religion, mysticism and they also “highlight the importance of interpersonal exchange in the restoration of sight.”

Pointing out the social context of blindness in the Synge play, Dr. Adar notes that “the couple’s attempt to integrate into the life of the village as seeing people is short-lived and ends in disappointment and a return to blindness.”

Further, “the failure of a cure is due to moral and social reasons, not physical or cognitive ones… Ironically, the saint who gives them sight, and who portrays himself as forgiving and generous, is the one instigating the villagers to chase the blind couple away at the end of the play. The blind couple had their eyes opened to the deceitfulness and narrow-mindedness of their community, and this revelation creates an irreparable rift between them and their neighbours.”

The scenario of the play raises the question of presumptions of a superior and ‘normal’ life in the world of sighted people, which the couple rejects. It also contains a rebuke of the status of the saint (and thus, religion) in arbitrating changes in physical senses. In this way, Synge carries on the philosophical discussion begun three centuries earlier in Ireland by Molyneux and then Berkeley thereafter.

Philosophy of Vision in Beckett

Moving on to Beckett’s Rough for Theatre I (which debuted in October 1958), Dr. Adar notes that this very different play features two anonymous characters: it “is set in a post-apocalyptic urban space, where A, a blind beggar, is playing his fiddle on a street corner. B, a cripple in a wheelchair arrives to see where the music is coming from.”

While B realizes it might be wise to “join forces” with the bling character, A is unmoved by B’s attempts: “unlike the blind beggar in Yeats’s play, however, A is not exclusively interested in material things and is asking B for more information about the world around him.”

A asks ‘how the trees are doing.’ Even this simple inquiry has its roots in the Irish philosophy of vision, it turns out: “trees are a motif that may suggest nature, regeneration, or even a source of food,” the scholar continues. “But they are also a popular example of a remote object in treatises on optics. Berkeley writes about “the magnitude of anything, for instance a tree or a house” (Berkeley 2000a: 23).”

Regardless of whether Beckett had Berkeley in mind (and his play does not overly mention the Molyneux Problem), the playwright touches on certain aspects of the inquiry.

While stating he has never been able to see, A nevertheless insists on asking B questions about the look and color of things, which results in some argumentative exchanges but no new revelations. Yet here too a kernel of comparative epistemology underlies it:

“A’s preoccupation with external appearances also calls to mind the Douls from Synge’s The Well of the Saints but more importantly, he is a blind man who wishes to see,” the scholar contrasts.m“His desire for knowledge is directed at practical things, but also at general information about the world.”

The moral of this particular play is starkly different, and involves the possibility of cooperation and compassion, rather than ritually, mystically administered knowledge, and also the possible future reduction of errors. B proposes that he could describe the visual world, if only A would push his wheelchair along- leading A to marvel that he might then not get lost anymore. As Dr. Adar notes:

“in Beckett’s bleak outlook there is no moment in which truth is revealed, be it the scientific truth of the medical profession, a mystical truth of God, or a personal truth about one’s partner.”

So there you have it- Synge and Beckett, Beckett and Synge.

As said above, I had no idea how I would unite the two playwrights when I started this research yesterday- only that I would find a way to discuss them together. Rather miraculously, Dr. Adar’s fine article, the implications of which I will be no doubt considering for a long time to come, presented itself.

Even if today’s article was not the lightest or most cheerful of this series, I still feel better for having written it; I feel like I learned something, though exactly what, I do not yet know. And… it’s not over yet. Now for the fun part.

Indeed, it would be remiss me of me to end without mentioning some Europe travel tips for visitors seeking out the legacies of these two great masters.

Synge and Beckett: Travel Tips

The most iconic place in Dublin associated with J.M. Synge must be the Abbey Theatre, where visitors can take in a play even now. Although a 1951 fire forced it to change addresses, it’s the same institution, and the legacy of the grand theatre first opened in December 1904 lives on.

Trinity College keeps a Synge research collection in Dublin, with important documents relating to the playwright and his works.

If you want to really get the full experience of Synge’s writing, while also getting away from it all, head to the remote Inishmaan Island (one of the west-coast Aran Islands off of Galway), where Synge actually wrote. The three-centuries old restored cottage (known as Teach Synge, website here) where he did so is the place to feel the Atlantic sea-spray and perhaps, hear a bit of the Gaelic.

As for Samuel Beckett, who always shied away from attention and disliked being celebrated, Trinity College’s drama school operates the Samuel Beckett Theatre; he doubtless would find that a more fitting (and less ostentatious) an edifice than the Samuel Beckett Bridge, raised over the River Liffey in 2009.

Last May, the Irish Times reported that Beckett’s stately childhood home in Foxrock, Dublin was going up for auction for almost 4 million euros. I haven’t found how that ended up, but the article does contain some lovely photos of the house and its interior, an inspiration for some of his works.

Of course, savvy Beckett connoisseurs will already know that a trip across the English Channel to Paris is required for seeing other sites related to Beckett. In fact, there are even a whole guides to ‘Beckett’s Paris,’ such as this one from 2020 by Deborah O’Donoghue. A rather terminal attraction in Paris is Beckett’s grave, a photo and directions to which are here.

Further, scholars can note that there is an official Samuel Beckett Society.

Finally, I came across the below recently-posted short gem from Samuel Beckett’s authorized biographer, Reading University Emeritus Professor of French, James Knowlson. It serves as a reminder that when it comes to serious Beckett studies, some of the best sites are neither in Ireland nor France, but in England.

Here, the University of Reading, a trustee of the Beckett International Foundation, maintains an extensive collection of Beckett-related archives. These have just been increased, with Knowlson’s donation of more than seven hours of previously-unreleased audiotaped conversation with the great playwright, which apparently include discussions of his WW resistance efforts.

So that’s all for today. What started with simply a general goal, to link Synge and Beckett somehow in a single piece, came together in a rather unexpected and miraculous way- even accepting Dr. Adar’s quip that “inevitably, a Beckett play allows for no miracles…”