Edgar Allan Poe and the Horror of Dutch Painting

When detective-fiction work led to scholarly insight on “The Masque of the Red Death”

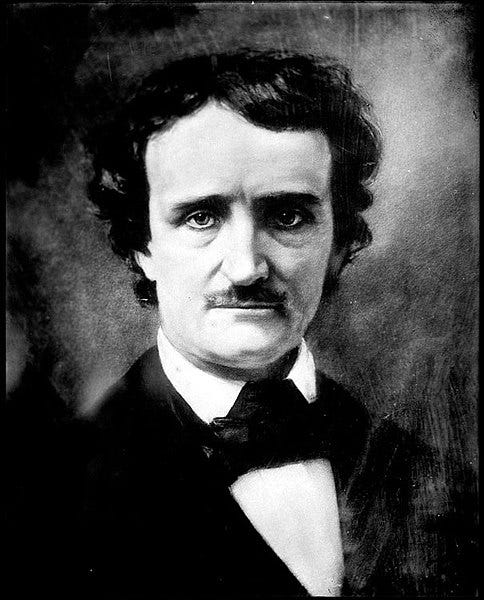

October 7, 2024 marked the 175th anniversary of the death of Edgar Allan Poe, in circumstances still mysterious, in the Baltimore of 1849. Given the pace of global change since that time, it is astonishing to note how, in many ways, we still inhabit Poe’s world; for if not the sole initiator, he did play a major role in influencing the future development of genres as diverse as Gothic Horror, detective fiction, dark romance, science-fiction, the supernatural, rhetoric, reviews and more.

Today’s special tribute, therefore, both discusses a specific case of Poe’s influence on my own writing (thus continuing the announced series), and also examines a 2019 scholarly essay on Poe. The latter will help both Poe enthusiasts and you fiction writers inspired by him, revealing new artistic overlap that sets an example for anyone’s writings. As it turned out, my research exploration open up new questions of historic import on Poe’s specific writing process in two 1842 stories. Edgar may be gone, but his ghost still has plenty of riddles for us now.

A Question: What’s Needed to Make a Great Story an Enduring Great Story?

I’d guess they’d have to be revolutionary in some way. Such stories contain within them something essential that reverberates down the ages, while not actually repeating, since world conditions change. They can thus be perceived as equally intolerable, for different reasons, to readers of different times and contexts.

And so with that famed Gothic tale, “The Masque of the Red Death,” first published in May 1842 in Graham’s Magazine. Today’s exploration of this story both illuminates the influence of this piece (and Poe generally) on my Detective Grigoris novel’s origins, and also delves into some fascinating published scholarship by an academic expert on Poe. Specifically, this concerns a new study on Poe’s use of the visual arts in crafting his apocalyptic tale. For those of you who are authors of Gothic Horror, this research may be useful in your own works.

There’s also a historical aspect. This literary journey back through time, we shall find, opens up a still largely-undiscovered world of pre-Civil War America, its vibrant arts scene, and how a trans-Atlantic art culture influenced authors such as Poe, whose work was affected by a lifelong affinity for beauty and the visual arts—but always recast in writing that was surprising, new and innovative.

Context: The 2020 Pandemic, the ‘Red Death,’ the Origins of my Detective Novel and my Poe Research

In summer 2021, while laid low during the pandemic and envisioning how to write a detective novel (the now-realized first Detective Grigoris manuscript), I began extensive readings (and listenings) of relevant works, inevitably leading to Poe. Aside from enjoying his early contributions to the detective-fiction genre, I was amused by that tale most appropriate tale for that time, “The Masque of the Red Death.” Aside from its topicality of plague and privilege, something about the shrill and sustained rhetorical tone of narrative, plus the use of colors and scenery, and its fundamental finality seemed very well done.

As you may know, in this allegory of human hubris, the aristocratic Prince Prospero and his large party of fellow nobles have taken refuge in a castellated abbey, to ride out the latest plague in style. After some time, they indulge in higher-than-thou masqued merriment, feeling safe from the ever-external ‘Red Death’ decimating the countryside.

Poe’s retelling features color-coded rooms, clocks, lavish tapestries and other elements of interior decoration that sent my travel-writer’s imagination into a fevered delight. Indeed, both Poe’s description and the plot were instantly seized by my memory for use in a future work; but we will have to wait, as the proper place will be the fifth installment of the Detective Grigoris series, to keep up with the times (as you recall, novel one begins in 1999).

In Poe’s tale, an unknown masqued stranger finally wanders through all the halls, angering the guests and Prince Prospero, whose own authority and weaponry are useless against this silent mystery guest; for he embodies the Red Death itself, and by the horrifying end, the party-goers fall, one by one. I’ve put below Christopher Lee’s inspired retelling from YouTube for your listening entertainment.

Further, though it wasn’t apparent at the time, my re-appraisal of “The Masque” in 2021 was good luck for the future detective series. For during the pandemic, I was envisioning a different novel, in which a Greek detective was just a minor character. However, reading the Poe tale actually changed my whole concept. It opened up an entire story-scenario that elevated the Greek detective to the role of protagonist, in a very different book, all because of one future adventure in which he’d star, in a nwe adaptation of he Poe story (as said, in the fifth nvoel).

So… without the pandemic and Edgar Allan Poe arriving at the same time, there would likely have never been a Detective Grigoris novel.

The Power of Painting: Poe, the Vanitas Style, and the Dutch Masters

Just as he engaged with other art forms and social trends in his general work, Poe also transferred the visual and moral elements of a certain kind of painting to his prose. I understood this more concretely after a Poe scholar in late 2021 suggested I read an article by Brett Zimmerman, Emeritus Professor of Literature at York University, Canada. (The following sections quote from his 2019 article, the full citation of which is below).

Zimmerman’s article argues that in writing “The Masque of the Red Death,” Poe took inspiration from paintings of the ‘vanitas’ style. Often associated with the 17th-century Dutch Golden Age, the ‘vanitas’ style had a moralistic grounding, using symbolic imagery to illustrate the inescapable nature of death and thus counseled pious wisdom in human action instead of vain, opulent or indulgent behavior.

Poe lived from 1809-1849, making the Dutch Golden Age sufficiently archaic to appeal to his Gothic imagination. As Zimmerman notes, Poe was a “prose-painter” intrigued by the symbolic element of these paintings, a writer whose critical mindset meant he “despised the blatantly moralistic in art.” The more subtle style of Dutch vanitas paintings, the scholar argues, is clearly reflected in “The Masque” and at least two other Poe stories he analyzes. At the end, I will argue that the influence is clear in a third, contemporaneous Poe tale as well.

Skulls and Skeletons in Medieval and later European Art

Zimmerman notes the artistic use of memento mori (Latin for ‘remember that you must die’) in such works. The Tate Gallery website recalls that typical paintings in this genre might depict skulls, clocks, hourglasses and so on. Skeleton as memento mori had existed since medieval times, as had the danse macabre, or ‘dance of death.’ This imagery is reused ironically by Poe, with his masque revelers despairing against their inevitable demise near story’s end. Zimmerman adds that in 16th-century art the skeleton was emphasized, and, in 17th century, the skull. In some cases, “a portrait of the deceased was actually replaced by a skull as a new kind of painting emerged: vanitas still life paintings.”

In later vanitas painting, the scholar adds, “entire scenes became allegories on the transitoriness of human existence.” Ultimately, this moralistic form of still-life artwork “developed into a fully-fledged genre in the 17th century.”

Biblical Dimensions, Poe’s 1844 Letter on Vanity, and a Famous Allusion

Another beloved standby of authors of Gothic Horror (and many other genres) is the odd Biblical allusion or reference. Poe draws on this source too, textually reinforcing the impact of narrated imagery that has, fundamentally, a common home in religiously-inspired European art.

Zimmerman quotes classicist Patrick de Rynck in explaining two Biblical passages related to the still-life vanitas genre’s development in the 17th century. Both are relevant to the vanitas theological concept of medieval European art—and in Poe’s story. The first is from Ecclesiastes: “Vanity of vanities, saith the preacher; all is vanity” (12:8). The second is from the Gospel of Matthew: “Lay not up for yourselves treasures upon earth, where moth and rust doth corrupt, and where thieves break through and steal: But lay up for yourselves treasures in heaven” (6:19–20).

Poe was also thinking of such passages, at least concerning “the impermanence of the temporal,” Zimmerman argues, noting that this is suggested in Poe’s letter (July 2, 1844) to James R. Lowell, in which the author wrote, “I really perceive the vanity about which most men merely prate—the vanity of the human o temporal life.”

Zimmerman thus describes the story as Poe’s “…literary version of the vanitas theme illustrating the Latin idea nascendo morimur (we are born to die).” Later in his article, he cites the direct Biblical allusion that Poe uses near the story’s epic denouement, with the sweeping presence of the masked intruder. Poe writes: “And now was acknowledged the presence of the Red Death. He had come like a thief in the night.”

The famous last phrase alludes to Thessalonians 5:2-4, where it states: “For you yourselves know perfectly that the day of the Lord so comes as a thief in the night. For when they say, ‘Peace and safety!’ then sudden destruction comes upon them, as labor pains upon a pregnant woman. And they shall not escape. But you, brethren, are not in darkness, so that this Day should overtake you as a thief.”

The Vanitas Style in Dutch Paintings and in Literature

The scholar then considers several vanitas-genre Dutch paintings as case studies, and three in particular: these are David Bailly’s Self-Portrait with Vanitas Symbols; Maria van Oosterwijck’s Vanitas—Still Life, and Antonio de Pereda y Salgado’s Allegory of Vanity. The scholar traces ‘symbolically meaningful’ elements that recur in these paintings and in Poe’s work.

The symbolic elements chosen by creators of vanitas paintings included objects alluding to hedonism, including dancing, music and alcohol or drinking vessels, including spilt ones. Combs and mirrors (sometimes cracked) are also common symbols, Zimmerman adds. And an overindulgence in the arts was even considered fair game for artists: “…appropriately, therefore, Bailly shows a palette hanging from a nail on the wall behind him,” the scholar notes.

Other common vanitas symbols are tobacco, pipes, jewelry, dice and playing cards. Silver, perfumes, expensive décor and silk, etc., are others. Interestingly, musical instruments appear in ‘more than half’ of the 15 overall vanitas paintings Zimmerman studied, noting the ‘fleeting’ aspect of music as a likely reason for its addition here, as well as the unstated and not very Christian aspect of carousing and carrying on that accompanies parties such as the one Poe describes in “The Masque.”

Drinking Cups, Books, and Moral Emptiness

In the paintings, when drinking cups are depicted as overturned, they convey the “literal meaning of vanity: emptiness.” Zimmerman goes through several more groupings of symbols, including bubbles, butterflies, smoke and candles, giving everything in a painting some subtle allegorical role. From this, it is simple enough to apply these images to the imaginations of the ‘prose-painter’ Poe, who (as he notes) was an avid lover of art.

Interestingly, books too are found in all three of the sample paintings, Zimmerman notes; they symbolize “not only the delights of reading but also knowledge, itself considered one of life’s guilty pleasures in this visual arts genre.” He adds, for the vanitas works, books “also represent the futility of human strivings and achievement and the impermanence of worldly knowledge and culture.” Here Zimmerman adds:

“Once again, Poe struck a vanitas note in the aforementioned letter to Lowell: ‘I have been too deeply conscious of the mutability and evanescence of temporal things, to give any continuous effort to anything—to be consistent in anything’ (CL 450).”

The Illusory Nature of Power in Vanitas Paintings and the Prince in his Abbey as Genre-Creator

Zimmerman then recalls several other Dutch paintings which portray how the great and powerful, like Poe’s Prince Prospero, are no match for ‘the great leveler.’ Dutch paintings feature the decapitated Charles I, for example, or include weapons just to highlight their uselessness against death. The latter is anticipatory of the action in “The Masque of the Red Death,” where the prince vainly tries to stab at the masked phantom who has arrived in the abbey, bringing with him the Red Death.

Poe knew what he was doing as a ‘prose-painter,’ and he even builds it into the story and its characters. Thus, along with having an architect and interior decorator for his castellated abbey, Prince Prospero has himself arranged all the conditions for his own genre still-life. Zimmerman adds:

“It is as if Prince Prospero and the ‘thousand hale and light-hearted friends from among the knights and dames of his court’ (M 670) are living within a vanitas painting: ‘The prince had provided all the appliances of pleasure. There were buffoons, there were improvisatori, there were ballet-dancers, there were musicians, there was Beauty, there was wine.’”

This, to me, replicates the ironic self-awareness of the aforementioned Dutch painter who refused to exclude the wasteful indulgence of art from his still-life painting. As the author, Poe affirms that he has complete control over the story, its setting and its outcome—and that that very outcome equally affirms the rule of his own eventual self-undoing as a mortal man.

In short, writing a story illustrative of vanitas painting invokes the same futility of vanity. It is an ironic and inescapable loop, which brings unstated self-awareness to the story; after all, Poe hated the obvious, and the direct didacticism of other writers of his time. But the imagery is captivating and fantastic, while it lasts; in the end, a reader of a popular magazine (which Graham’s was) could simply be entertained, and miss the deeper message. Such applications still apply to this story today, even in a much different era.

Lavish Tapestries and Time Symbols

The lavish décor of Prince Prospero’s abbey also includes its hung tapestries and carpets. Zimmerman notes that “Within the context of the vanitas tradition of the Dutch Golden Age, Poe probably knew that, in the seventeenth century, decorative fabrics such as draperies were brought into the Dutch Republic through trade and commerce; they were therefore expensive signs of wealth, pride, and status.”

Another major symbol of vanitas painting—time and clocks—is pointed out by Zimmerman in Poe’s description of what stands at the end of the abbey’s final, black-colored apartment. Poe writes: “there stood against the western wall, a gigantic clock of ebony. Its pendulum swung to and fro with a dull, heavy, monotonous clang” (M 672).”

And, as depicted in Dutch paintings, the narrated passing of time (the chime of the clock) has a dramatic function. It makes the party-goers pensive and disturbed, though they know not why. This sets up the tension for the increasingly dramatic mood before the ebony clock chimes midnight at story’s end and the Red Death has run rampant over all.

Here Zimmerman reminds of Jean-Paul Weber’s classic description of Poe as the ‘maniac of time,’ and underscores how crucial time and its workings are to his rhetoric and structure.

Did Poe Actually See Vanitas Artworks? A New Line of Inquiry

After reading Professor Zimmerman’s article, I became fascinated with the following question: what are the realistic chances that Edgar Allan Poe actually saw a classic Dutch vanitas painting, or even some sort of copy, in early 19th-century America?

The short answer: we don’t know—though several scenarios are possible. And this makes for good future research.

In his article, Zimmerman mentions Barbara Cantalupo’s Poe and the Visual Arts (2014), the first book to examine in detail the author’s relation with the visual arts. While clarifying that Cantalupo does not specify the vanitas genre, Zimmerman writes that she “demonstrates that he was exposed to and knowledgeable about a wide gallery of artists and paintings while living in Philadelphia and New York between 1838 and 1849.” More specifically, Zimmerman notes that:

“The Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts exhibited European as well as American art—and even if Poe had never viewed an actual painting by one of the classic masters, it is hard to believe that a writer so well acquainted with the visual arts, as Cantalupo proves him to have been, would not at least have been acquainted with the genre: ‘In Philadelphia the prominence of the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts provided a rich resource, as did Poe’s friendships with artists Felix O. C. Darley, John Sartain, John Gadsby Chapman, Thomas Sully, and the latter’s nephew Robert Sully’.”

Continuing on from this, I reached out to several more individual experts and research institutions. While there is still much work to be done, I have learned much and will offer here some possible areas of promising future research. Of course, the scholarship on Poe is so vast that it’s eminently possible my ‘discoveries’ are well-known to specialists, but anyhow, this is what I will say.

In the America of Poe’s writing life (1820s-1840s), both art galleries and private collections existed in important cities and even large towns. Aside from places like Boston, Philadelphia, and New York, these included Richmond, where scholars have informed me that contemporaneous newspaper archives attest to both private galleries and announcements for art auctions. Due to the close connections with Europe, and frequent trips by painters on commission (including those Poe knew), both the transmission of art and news about art to the New World was a fluid and ongoing process.

Poe was well connected with Richmond during parts of his life, and with the Sully family of painters; in fact, in the April 1842 issue of Graham’s Magazine, he cites the art of Sully (probably, the more famous uncle) in the two-page story “Life in Death” (better known as “The Oval Portrait,” the name it was republished under in 1845 and ever since).

This story is literally about art, and in a different way is more a meditation on the vanity of the arts than “The Masque of the Red Death.” However, it has additional narrative omission techniques that would require a separate study just to explain Poe’s singular genius on that little work. I’d prefer to study further the writing historiography process of both stories before making a conclusions.

Still, the fact that two art-focused stories with strong (if oblique) moral aspects were published by Poe within a month of one another indicates a strong likelihood that he had either recently read about art, seen art, or talked about it with an artist friend. Although his love of art was life-long, I would guess that something specific occurred in 1841 through early 1842 that turned Poe’s attention to narrative statements about the visual arts, as a “prose-painter,” in an indirect and non-didactic way that bequeathed both his and future generations with two remarkably vital stories.

Above Citations from:

Brett Zimmerman, ‘Such as I Have Painted:’ Poe, “The Masque of the Red Death,” and the Vanitas Genre,’ The Edgar Allan Poe Review, Vol. 20, No. 1, pp. 46-63 (2019), Pennsylvania State University.

Audio Narration: Listen Here to “The Masque of the Red Death”

There are numerous narrations of today’s story. One particularly famous oration of Poe’s “The Masque of the Red Death” is that of Christopher Lee here:

A tour de force!

Interesting connection between Poe & the vanitas tradition. I look forward to listening to the reading of The Masque . . .